Investing according to environmental, social and governance principles is maturing into a distinct discipline.

Robust research results dispute the conventional wisdom about performance trade-offs. If your institution has yet to consider ESG seriously, it may be time to take a closer look.

For decades, institutional investors have struggled with the challenges posed by “responsible” investing. These investors faced a wide range of issues—definition, measurement and objective-setting among them. But, the most pervasive question was—and continues to be—whether socially responsible investing (SRI) screens or today’s more all-encompassing environmental, social and governance (ESG) factors help or hurt long-term investment performance.

On one hand, investment committees are stewards of long-term asset pools and have a principal responsibility to maximize investment performance subject to the risk tolerances that they have identified in their investment policy statements.

The conventional wisdom intuits that anything that tends to limit investment options has two potential problems—one, lower performance and, two, higher risk.

Conventional wisdom may not be accurate, however, when it comes to ESG. This article will address the issues in three ways: first, by seeking to facilitate conversation among investment committees by setting forth some basic definitions and background; second, by looking at the obstacles that may be standing in the way of greater adoption of ESG principles and practices, including trends in responsible investing; and, third, by offering some practical ideas about implementing an ESG program at your institution.

ESG can be viewed as a natural extension of fiduciary care in many ways.

Terminology a cause of confusion

There are a great many terms referring in some way to practices related to responsible investing: socially responsible investing; mission-related investing; impact investing; integrated reporting; and investing according to environmental, social and governance principles. These terms are often grouped under the same category of responsible investing, but this generalization is misleading because it overlooks the fact that what these terms mean in practice is very different. This proliferation of terms is a complicating factor for many who are new to the field. Perhaps the two most common terms are SRI and ESG (see below for further details).

SRI is a process that screens out undesirable companies or industries from the investable universe based on particular moral or ethical criteria; investment managers are then free to apply their normal analytical process to the remaining stocks or bonds. ESG refers to a broader approach that adds environmental, social and governance factors to the other tools in a manager’s investment toolbox.

ESG has been developed over the last decade and has been promoted by the United Nations Principles for Responsible Investing (UN PRI) initiative. ESG is generally agreed to be the broader and more all-encompassing term, as it comprehensively incorporates sound environment, principled social behavior and good governance factors into investment analysis and decision-making. Including ESG factors as part of their investment analysis, institutional investors can feel confident that their portfolios are being invested with the objective of generating superior long-term returns. Whereas earlier forms of responsible investing largely focused on portfolio exclusions, responsible investing today is more likely to include forward-looking, long-term sustainable factors with the intent of finding investments that will add value.

Evolving into today's ESG

Perhaps one reason that responsible investing has a broad vocabulary is the fact that it has gradually developed over many years and evolved with the changing times. Responsible investing traces its roots to the colonial era with religious groups refusing to invest in the slave trade. SRI evolved in the 1960s, a decade marked by history-changing movements, including civil rights, environmental concerns, feminist issues and anti-war protests.

In the 1970s, environmental awareness continued to grow, and the first funds to focus on issues beyond sin screens were introduced.

The 1980s saw developments on many fronts, starting with international concerns over apartheid, with investor pressure leading several corporations to leave South Africa. Occupational safety and health standards also became a growing concern.

By the mid-1990s, there were about 55 SRI mutual funds and about $12 billion in SRI assets. Tobacco divestment drove much of the activity during the decade. Thus far in the 21st century, climate change and humanitarian crises in various countries have risen as new concerns. Blatant corporate misbehavior also captured headlines—Enron and WorldCom being prime examples.

A landmark occurred in 2006, when the United Nations launched the previously mentioned Principles for Responsible Investing (PRI), an initiative asserting the importance of ESG issues in investment decision-making. The initiative asks that signatories abide by six principles:

- Incorporate ESG factors into investment analysis and decision-making

- Be active owners with respect to ESG

- Seek appropriate disclosure on ESG issues from companies

- Promote the acceptance of ESG principles

- Work together to enhance the implementation of ESG

- Report on ESG activities and progress toward implementing ESG principles

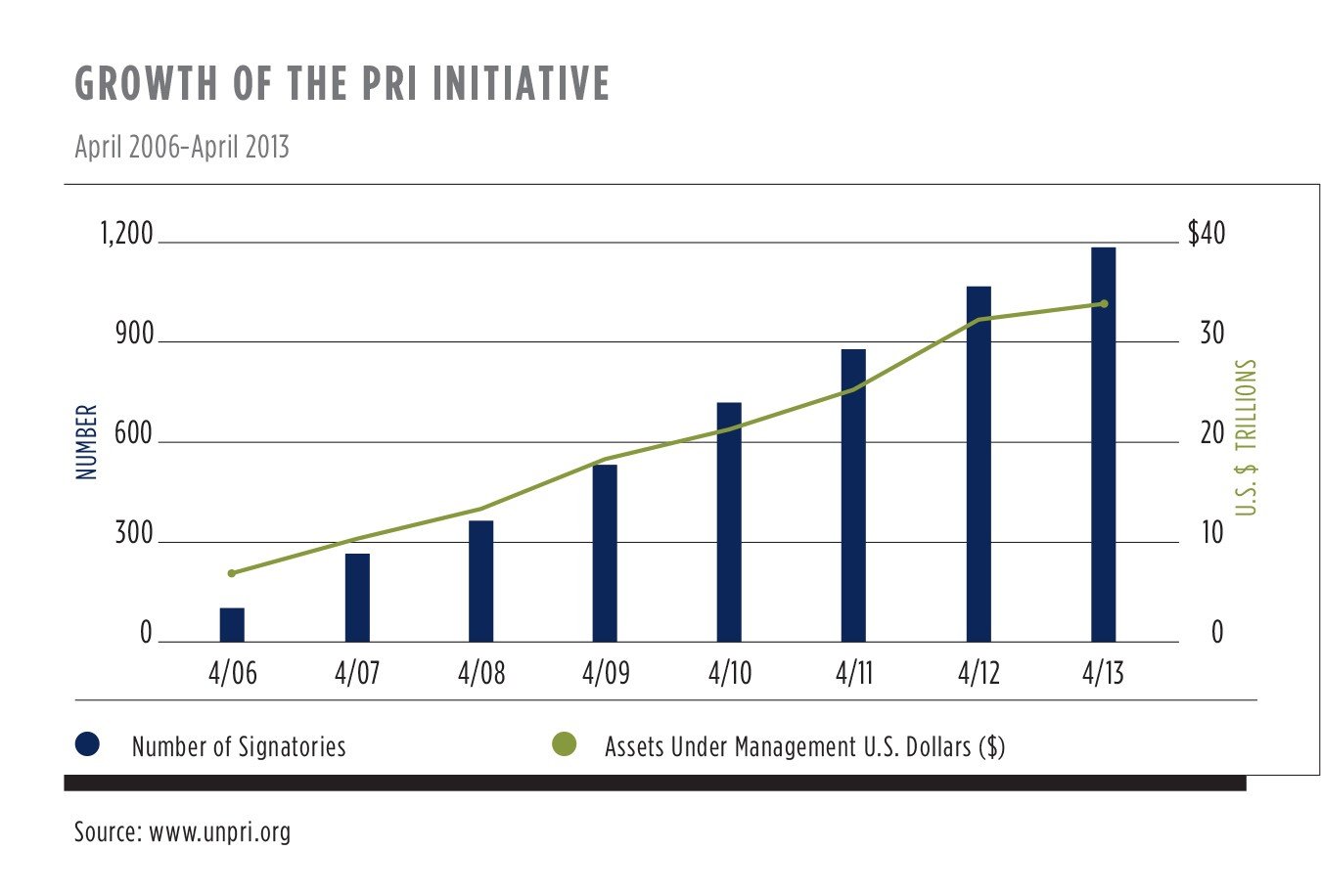

Today, according to data from UN PRI, there are about 1,180 signatories to the Principles. According to UN PRI, these institutions represent $32 trillion in assets, or 15 percent of the world’s investable assets, up from $4 trillion at PRI’s launch in 2006. In 2009, the United Nations Environment Programme Financial Initiative released a report confirming that “responsible investment, active ownership and the promotion of sustainable business practices should be a routine part of all investment arrangements.”

ESG and fiduciary responsibility

Any discussion of integrating ESG analysis into the investment process and its impact on portfolio performance has to emphasize trustees’ fiduciary responsibility.

Historically, the assumption has been that constraining the investment universe in any way would probably result in lower performance or an increase in a portfolio’s risk. However, the overwhelming majority of current academic studies show that ESG does not imply a performance trade-off, particularly for long-term stewards of capital.

Consideration of ESG criteria can be viewed as a natural extension of fiduciary care because it focuses on factors that may be material to long-term returns.

Economic benefits from ESG

It stands to reason that companies that are reducing greenhouse gas emissions will lower fuel and energy costs; that saving water will reduce water costs; and that reducing use of raw materials will lower input costs. When Wal-Mart required its suppliers of detergent to provide a more concentrated formula, it benefited from lower packaging and transportation costs.

Starbucks’ focus on the sustainability of coffee growing is critical to its long-term success and ability to maintain the quality and quantity of its strategically critical coffee supply.

Date support ESG advantages

But, what of actual data? Deutsche Bank published a study of academic literature on sustainable investing in June 2012.

This extensive project surveyed more than 100 research studies about integrating ESG analysis, SRI and other responsible investing strategies into the investment process. The report’s findings were compelling for ESG and cautionary for SRI:

- One hundred percent of the academic studies agree that companies with high ratings for corporate social responsibility and ESG have a lower cost of capital in terms of debt and equity.

- Eighty-nine percent of the studies examined show that companies with high ratings for ESG factors exhibit market-based outperformance.

- Eighty-eight percent of studies of actual SRI fund returns show neutral or mixed results.

Index publishers have begun to capture the results of ESG strategies. MSCI has launched a new set of ESG indices to provide benchmarks for investors using ESG-based investment programs.

In general, MSCI includes companies with higher ESG ratings that comprise 50 percent of the market capitalization in each sector of an underlying index. The result is that companies with the lowest ESG ratings are dropped from the index.

The MSCI World ESG Index began in October 2007, and since inception the index has had annualized returns of 0.7 percent through March 2013. For the same time period the MSCI World Index returned 0.4 percent.

The longest-running SRI index, the MSCI KLD 400 Social Index, traces its roots to 1990. It comprises 400 companies drawn from a universe of the 3,000 largest U.S. public equities by market capitalization and is designed to exclude companies in a number of sectors including alcohol, tobacco, gambling, weapons and others. Since inception in May 1990 through March 2013, the MSCI KLD 400 Social Index returned 9.9 percent annually compared with 9.5 percent for the MSCI USA Index over the same time period.

Traditional equities have had the longest record of exposure to ESG considerations but a growing number of fixed income funds are beginning to consider the impact of ESG factors on their portfolios. Although some managers are starting to offer ESG-designated products akin to the 250 socially screened mutual funds that currently exist in the U.S., we expect an increasing number of managers to incorporate ESG into their fundamental investment processes so that there will be little difference between how they manage the investment process for an ESG-specific fund or any other program offered by the same manager.

ESG and alternative investments

With many institutions investing the majority of their assets in alternative strategies, this area also demands attention. Can institutions that believe in the materiality of ESG factors invest in private equity and hedge funds?

The answer is that it’s becoming easier as more managers are becoming cognizant of the impact of ESG issues. A number of the early signatories to the UN PRI were private equity firms. In reality, these private equity managers exercise significantly more influence over their portfolio companies than managers investing in publicly traded securities.

Private equity managers also have a longer-term investment horizon, allowing them to implement ESG components more effectively. In 2008, private equity firm KKR launched its Green Portfolio Program comprising 24 portfolio companies focused on improving their environmental and business performance around the world. These are not necessarily companies in green industries, but rather, they cover a wide number of industries: automotive, beverages, retail, manufacturing, telecom and others.

Through efforts in energy and water efficiency, better waste management and operational improvements, the portfolio companies have reported significant financial savings as well as reductions in greenhouse gas emissions, solid waste and water usage.

Private Equity guidelines

Recently, the UN PRI and a group of 40 limited partners, 20 industry associations and 10 leading general partners published a new ESG Framework for Private Equity. The framework is aligned with the PRI’s efforts to encourage informed and systematic dialogue between limited partners (LPs) and general partners (GPs) about how ESG factors are considered in private equity investment activities.

The document outlines eight objectives common to many LPs who want more structured ESG disclosures within their private equity investments. The first five objectives relate to the fund due diligence process, and the next three relate to disclosures during the life of the fund. Guidance is also provided on the disclosure of information around unexpected events that might pose reputation risks to an LP, GP or portfolio company.

Work is also being done with hedge funds, whose investment horizon is generally shorter than a private equity fund. Intuitively, hedge fund managers would seem less predisposed to ESG investing. But, more of them have been willing to offer separate share classes or set up other mechanisms for clients looking to incorporate responsible investing in their portfolios. According to a study by the Forum for Sustainable and Responsible Investment (US SIF), overall, alternative assets managed in accord with ESG principles are still fairly small—a little more than $130 billion—but the rate of growth is swift, with a 250 percent increase from the end of 2009 to 2012.

Manager Rating System

Mercer Consulting has developed a process to rate investment managers based on integration of ESG issues. Since 2006, the firm has rated over 5,000 managers, assigning them to one of four categories. Of the managers analyzed, 57 percent are in listed equities, 20 percent in fixed income and 23 percent in alternative strategies. Earning a top ranking is difficult.

Only 9 percent of investment strategies score in the top two categories. But, by asset class, private equity has the highest proportion of highly rated ESG strategies.

Ways to get started

In such a broad and rapidly evolving field, getting started can appear to be a formidable challenge. The good news is that there are organizations and networks that can help, not to mention the option of learning about the real world experience of peer organizations that have integrated responsible investing tools into their investment processes.

A first step might be to assemble a group of people in your organization—a trustee, a staff member, students or faculty members— interested in learning more about ESG and assisting the committee or the endowment office to better understand how ESG factors may be material to investment performance.

Because there is such a wide array of ESG issues, Mercer Consulting suggests that one starting point is to look at issues that are important to your organization both in terms of investment opportunities/risks and mission—focusing first on those areas where the two align. Individuals or groups within your organization spearheading such an effort will find plenty of help, as there are a great many networks that can provide useful information and insight.

Among them are the UN Principles for Responsible Investment, as well as investment managers and service providers involved in the ESG initiative. Several associations and organizations have been set up to help endowments and foundations think about how to incorporate ESG factors into their investment process. Some of these organizations include the Sustainable Investment Research Institute, the Tellus Institute, the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board and US SIF (formerly the Social Investment Forum). Many offer extensive information on different types of responsible investing through access to research, workshops, webcasts and conferences.

Institutions may also choose to work with an outside adviser or consulting firm with knowledge and experience in analyzing ESG factors. As an institution’s approach to ESG develops, it will be important to determine how to monitor and measure exposure to ESG factors. This is not a one-size-fits-all process, so institutions will have to determine the approach to ESG that is right for them.

Conclusion

Commonfund has been a long-term advocate of the concept of intergenerational equity—the principle that endowments and foundations balance the needs of the present generation with the needs of future generations. This long-term approach to the sustainability of missions places great importance on the management of investment portfolios—giving your organization the best chance of fulfilling its mission now and in the future. We believe that organizations that do good must also do well in order to perpetuate their influence. By incorporating ESG factors into the investment process, organizations provide additional support to their goal of doing well and doing good.

What are the differences between SRI and ESG?

Socially responsible investing (SRI) has been around for a long time. Environmental, social and governance (ESG) factors are a newer concept. As a new concept, the various aspects of ESG may be interpreted differently by some organizations, but here are a few basic differences.

SRI

PRINCIPLES FOCUS

Investments driven first by ethical values.

USE NEGATIVE SCREENS

Organizations prohibit investment in certain companies or industries depending on the investor’s criteria. For example, some health-related organizations prohibit investment in tobacco companies.

NARROW DEFINITION

SRI is typically more narrowly defined by the investor. For example, divest the portfolio of the top 200 fossil fuel companies.

DIFFERENT CRITERIA

SRI screens are different for different investors. Some organizations impose religious or ethical screens like no alcohol, gaming, or fetal tissue research companies. Tobacco screens are employed by some health-related organizations. Sudan, South Africa and weapons have been the focus of some divestment campaigns. But the key point is that different organizations have different priorities, so SRI criteria are not universal but very organization-specific.

ESG

RETURNS FOCUS

The inclusion of long-term sustainability factors guides investment research to identify companies with higher investment potential.

NO NEGATIVE SCREENS

Specific investments are not prohibited, but rather rankings are assigned to ESG factors for a company in any industry. These ESG rankings are used as part of the overall investment research process. Poor rankings do not necessarily exclude a company from investment but are cause for further evaluation and consideration.

BROADER DEFINITION

ESG incorporates a broad set of factors to guide security selection. For example, which natural resource companies are less likely to experience catastrophic events because of their environmental and safety practices?

MORE UNIVERSAL APPROACH

ESG is still in development, so the application of these factors will evolve, but the theory is that certain factors have broad applicability to all investment options. For example, good governance, strong shareholder rights, and transparency are positives for investors in any company.