On February 24, 2022, Russia fired the first shots of its unprovoked invasion of Ukraine, setting off a cascade of global changes that systemically altered the world order. The horrific humanitarian crisis borne by the Ukrainians and the geopolitical consequences of the invasion are likely to be a global issue for many years. One key change is the return of the question of energy security, once again at the forefront of our global economic consciousness.

Sanctions on Russian oil and gas, followed by increasingly punitive Russian export reductions to Europe, have combined to place significant pressure on the sources of supply the world became dependent on for many years. From spending greater than $5 per gallon of gasoline in the United States to paying three times what you are accustomed to on your power utility bill in Europe, politicians, businesses and consumers are increasingly concerned about the repercussions of energy security.

What is energy security?

The International Energy Agency (or “IEA”) defines energy security as, “the uninterrupted availability of energy sources at an affordable price.” With discussions of potential energy rationing in Germany1 and sky-high prices for a variety of energy commodities around the world, energy security as defined by the IEA is at risk for some consumers in a way not experienced since the OPEC-led oil embargo in 1973-1974.

The implications of the debate surrounding energy security are inextricably tied to geopolitics, but the investment world should recognize the opportunity this may offer investors during this turbulent and uncertain time. When looking at markets like the United States and Europe, there exists a clear need for more domestic hydrocarbon production. Such production will be critical to sustaining affordable access to energy. Additionally, economically competitive sources of sustainable energy—sourced from both power production via renewables and demand reduction from energy efficiency—should be prioritized even further to enhance the path to energy security.

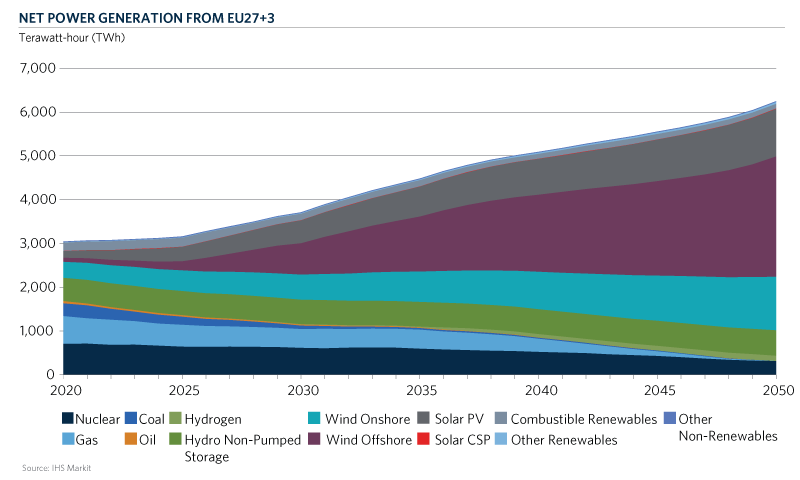

Europe provides the starkest example of this dynamic. When we look at the EU’s primary energy consumption by fuel, non-fossil fuel related sources (renewables, hydroelectricity and nuclear energy) accounted for roughly 30 percent of the EU’s consumption in 2021. As energy demand is expected to continue to grow, renewables are expected to (a) help provide a source for that growth and (b) displace some of the other sources of energy investing on the continent. At the same time, the EU had an energy import dependency rate of 57.5 percent in 2020 with Russia meeting 26.9 percent of Europe’s demand for oil, 46.7 percent of its coal demand and 41.1 percent of its natural gas demand.2

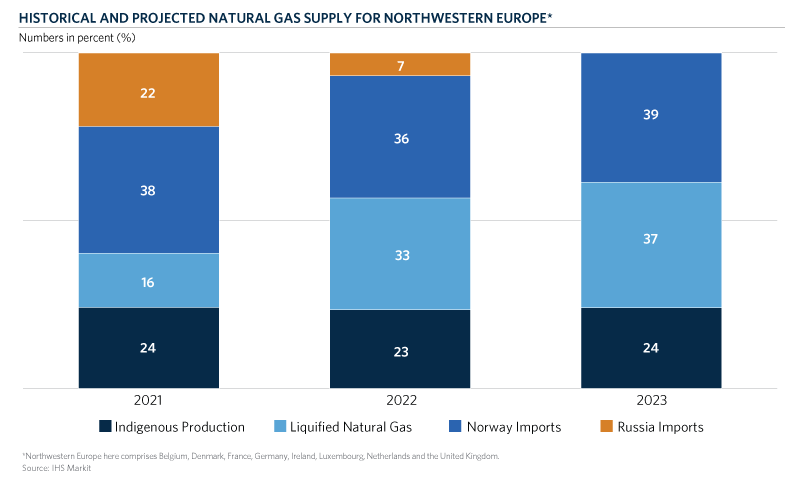

Today’s crisis represents the culmination of years of concern about the stability of supply to Europe from a potentially adversarial supplier in Russia. Going forward, if the priority for the EU is to reduce energy dependency from unfriendly jurisdictions, governments there can pursue a combination of (i) increasing domestic supply of conventional energy sources, (ii) pursuing imports from friendlier suppliers and (iii) continuing to develop renewables and build out energy efficiency domestically to reduce dependence on fossil fuels. There will ultimately be an array of policy choices made across Europe as this crisis unfolds over the next year – but any and all of those paths may serve to create investment opportunities on both sides of the Atlantic.

It cannot be ignored that efforts to curb current and future carbon emissions have created conflicting signals to the market with respect to energy security. While the oil and gas reserves in places like Europe are more limited, the North Sea continues to provide a low-cost source of oil and gas to much of the continent. This source of supply has also faced significant resistance to new developments (particularly in the United Kingdom). In March 2022, the United Kingdom’s Chief Secretary to the Treasury, Simon Clarke, implied the need to chart a new course on balancing energy security with climate goals, stating, “The government is going to set out the energy security strategy in the coming weeks, but it involves doing more of all the things we need to do. It means more renewables, more nuclear, more oil and gas from the North Sea.”3 The UK is increasingly recognizing the benefits of secure, stable, and domestic production and will require investment capital accordingly.

The implications of these changes are not solely felt in Europe. Last year, the United States sent one-third of its LNG exports to Europe. During the first four months of 2022, it sent three quarters of it.4 As Europe looks to displace its heavy reliance on Russian natural gas, there’s an opportunity for (a) investment in the infrastructure to support further LNG development and (b) investment in continued development of U.S. natural gas reserves and production.

Traditional sources of energy—oil and gas—have taken most of the headlines in 2022, but they are not the only potential opportunity stemming from the return of energy security challenges. Continued renewable development has and will be an investment opportunity as costs have fallen and the technology has only improved. The European Commission envisions spending 210 billion euros over the next five years to put it on track to hit their target of 40 percent renewables by 2030.5 Investment capital will likely come from private markets, developers, banks and utilities. This demand isn’t limited to governments and regulators—corporations are an increasing source of offtake agreements for renewable power as they seek to both manage their energy costs and meet net zero targets.

In the wake of this market shock there has been a recent recognition from investors that a balanced approach to energy policy—and energy investing—may be in order. Climate change is a critical concern—and so too is energy security. There is again debate around Environmental, Social and Governance considerations relating to the origination of fossil fuel supplies. To that end, the EU Parliament moved in early July 2022 to include natural gas and nuclear power in the definition of “climate-friendly” investments, recognizing the need for a multi-faceted solution.6

Today, the world faces the most significant energy crisis seen in decades. The resultant realignment of energy interests and priorities may lead to greater energy security going forward. As governments seek to balance security and the environment, they will undoubtedly require significant investment, both public and private. There is no one, single solution—and maybe that proves to be the most important lesson of this crisis—that a diverse approach across the resource spectrum may offer governments, consumers and investors a better risk-adjusted approach to energy.