In early May, Commonfund had the opportunity to participate in the NACUBO Endowment Leadership Series by delivering a virtual learning session entitled, “Measuring Success with Private Equity”. The questions posed for the discussion included “How did private equity stack up against public-market returns?” and “How should investment committees be measuring these illiquid investments that are inherently different from publicly-traded investments?”

Three learning objectives were outlined for the session:

- Identify the unique set of return measures in private equity.

- Differentiate between gross and net returns in this alternative asset class.

- Define the different options for analyzing and benchmarking private equity returns.

I had the honor of moderating this discussion with Commonfund board member Jessica Brennan, Managing Director and Head of Client and Product Solutions at Onex Corp., Dr. Miriam Schmitter, Head of ex-U.S. Private Equity and member of the Commonfund Capital Investment Committee and Deborah Spalding, Chief Investment Officer for Commonfund Asset Management and chair of Commonfund Asset Allocation and Investment Committees.

How did private equity stack up against the public market?

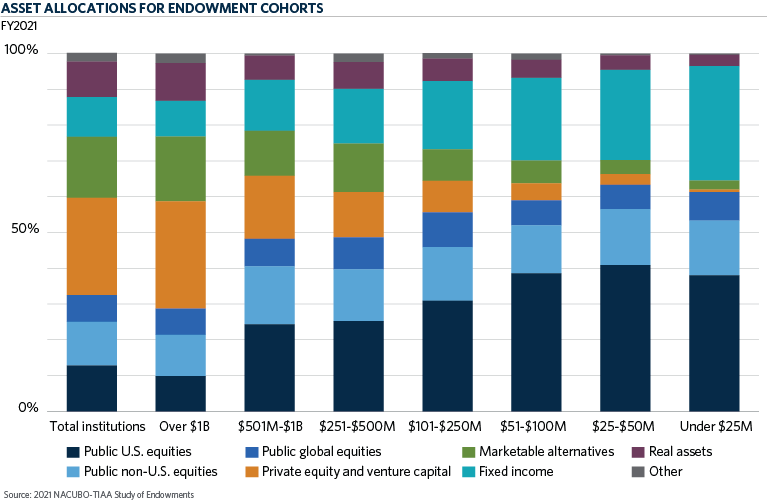

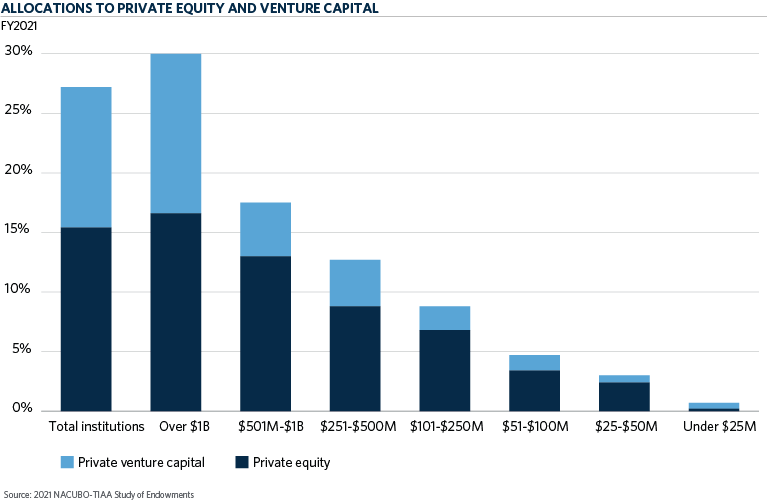

We shared information from the 2021 NACUBO Study of Endowments on the average asset allocation to private equity and venture capital. The study revealed that the largest allocation to private equity and venture capital is 30 percent for the endowments greater than $1B in size and the average for all cohorts is 27.2 percent.

In general, the breakout between private equity and venture capital allocations is about a 2/3rds, 1/3 split with heavier weighting to private equity.

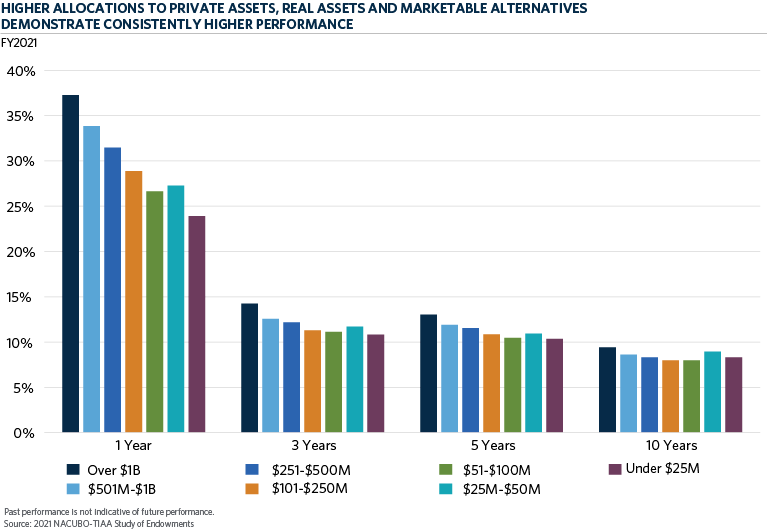

Another result of the NACUBO study indicated that higher allocations to private equity, real assets and marketable alternatives correlated to consistently higher performance across not only the last year, but also the 3-, 5- and 10-year time periods in most cases.

A live survey during the discussion revealed that 67 percent of participants believed market returns in 2022 would decrease from the prior year. Additionally, 51 percent of participants indicated that they would keep their private equity and venture capital allocations steady, whereas 30 percent of respondents shared that they were likely to increase their allocations in this area.

How should investment committees be measuring these illiquid investments that are inherently different from publicly traded investments? And how do fees factor into those discussions?

When discussing asset allocation and performance expectations Spalding noted, “You can’t time private assets. One-year return expectations don’t matter. The real question is can you get consistently compensated for taking on illiquidity?”

Brennan shared her perspectives on fees for the asset class, noting the differences in how management fees are charged today, some on committed capital and some on invested capital. She added, “while fees in the asset class have a reputation for being expensive, as investors look at the expenses that are charged, they are cognizant of the returns that the manager can generate, meaning they are less price sensitive for the highest performing managers and more price sensitive for lower performing managers with moderate returns.”

To this point, Schmitter added that fees, in some areas, and for certain types of investors, have become very politicized. As a result, some investors, such as large pension funds, have had to move away from investments in private equity and venture capital as it has driven up their overall fee exposure and created negative sentiment.

“When we look at the fee load, the thing we are really looking for is alignment. If funds are getting larger, fees really should come down. We look for managers that are really working for the carried interest.”

The measurement of performance to benchmarks should be based on net returns (i.e., returns after fees are subtracted). Investors also need to understand whether carried interest is paid on a European waterfall structure or an American-based schedule. Spalding noted, “investors need to focus on net returns. When you find talent, you should pay for that talent.”

Brennan shared her “go to” measurements in private equity, predominately net Internal Rate of Return (IRR), defined as the time series return of investments as well as multiple of invested capital (MOIC). A third measurement might include DPI, or distribution of paid in, in other words, the measure of every dollar that you have paid in, and what have you have gotten back on a net basis. Understanding the use of credit lines as well as valuation policies are also critical to understanding how managers are valuing their portfolios.

For investors that are looking to equate the private equity and venture capital aspects of their portfolio with the public orientation of their investments, public market equivalents or “PME” is a widely used measurement today. This approach takes the cash flows of private funds and assumes those same flows in a public index such as the S&P 500, enabling investors to determine if they have achieved a higher level of performance, an “illiquidity premium”, for holding illiquid assets in their portfolio.

Another dynamic of consideration is pacing. The market has seen managers coming back to market to raise new funds more quickly - this can create both concerns and opportunities for investors. The broad recommendation from the panel was to evaluate both the total invested capital as well as distributions from managers under consideration as well as looking at the universe of the “best” managers, vs. the “best available” managers. These measurements could be powerful factors for determining whether managers will be successful in follow on fundraising cycles.

Conclusion

While there are many factors to consider when building, selecting, and measuring private equity investments, a consistent, diversified, and disciplined approach to this asset class has proven to be successful over the long term. Importantly, fiduciaries with oversight of perpetual pools of capital have the opportunity to invest in illiquid asset classes, potentially gaining the premium they can provide, due to their long-term horizon.