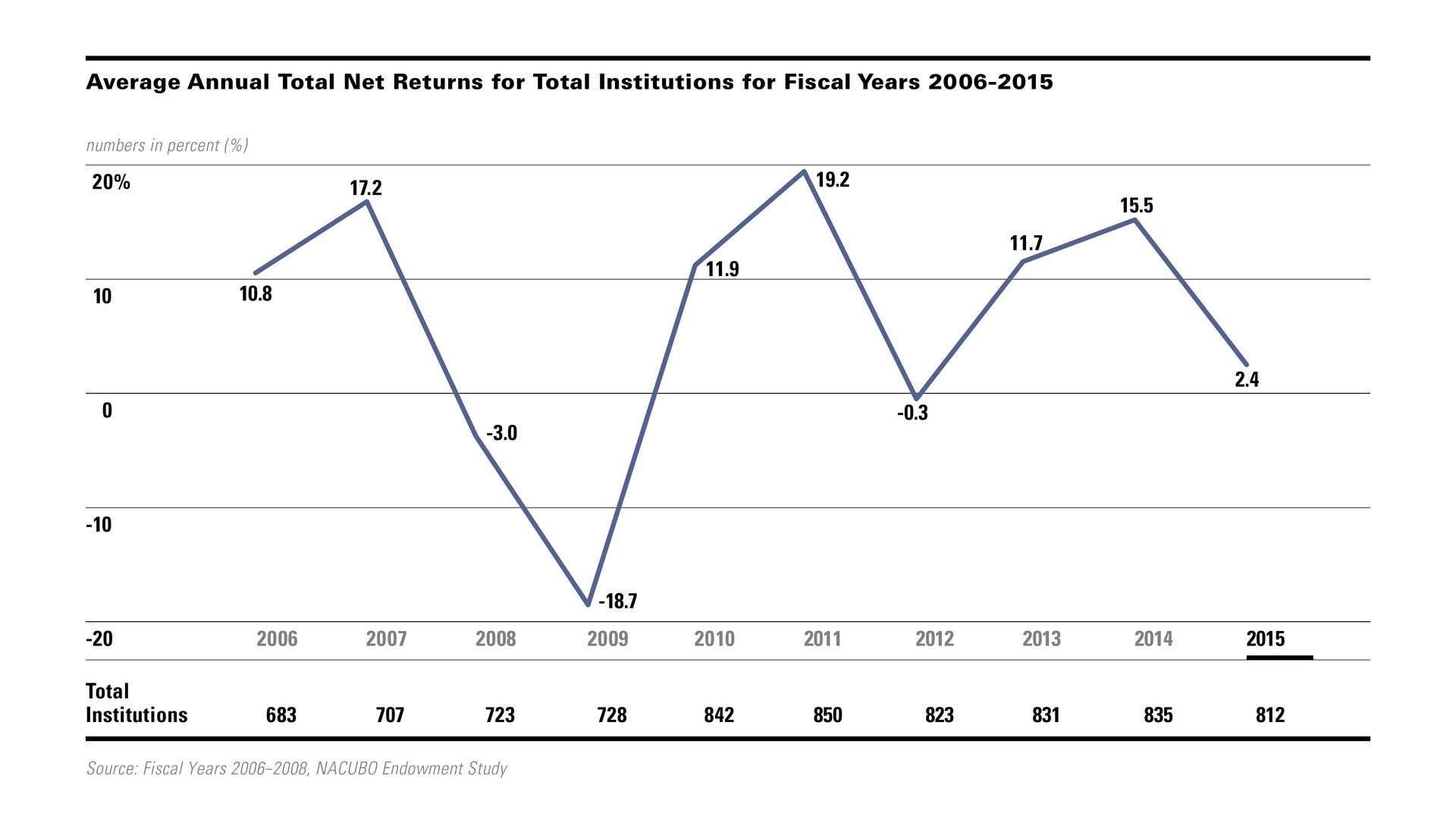

How long is the long term? A year ago, endowments appeared to many observers to have recovered from the losses suffered in the 2008-09 global financial crisis. Double-digit investment returns had been reported in every year except FY2012, donations had returned to their pre-crisis levels and the investment strategies of successful endowments were once again followed closely in the financial press.

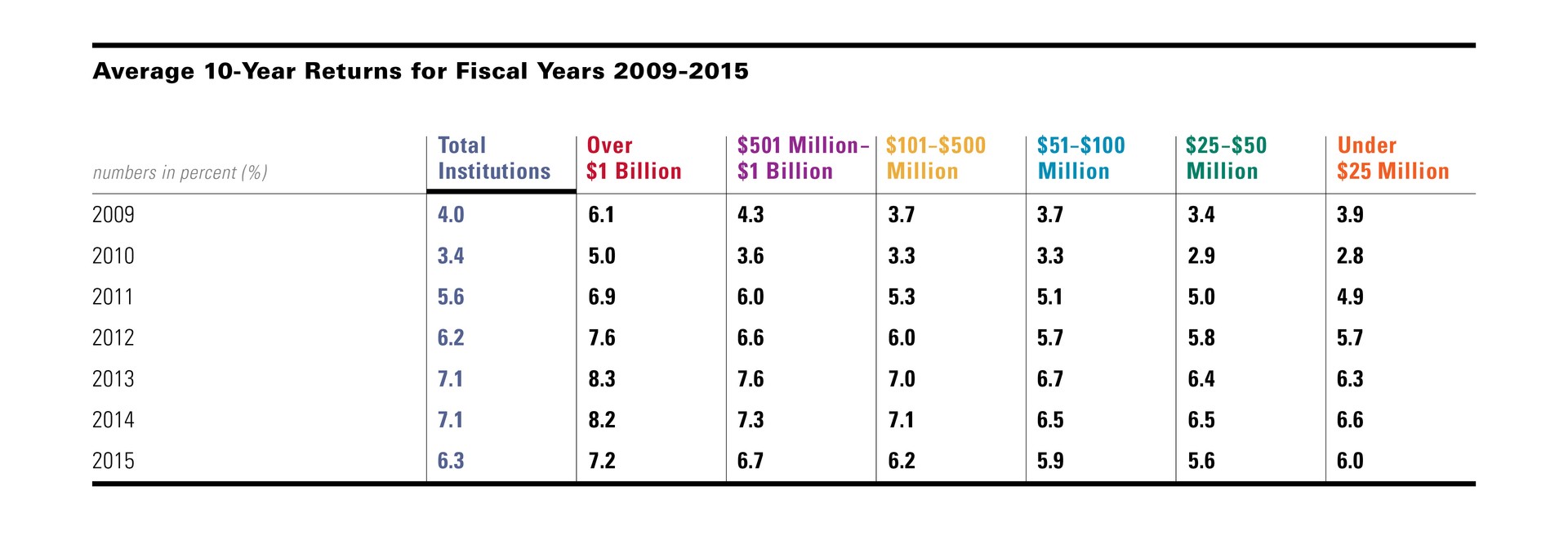

One-year returns make headlines, but most investment officers consider a 10-year horizon to be a more appropriate period over which to judge success or failure. Somewhat longer than the typical seven-year market cycle, a 10-year period can even encompass two shorter market cycles; for this reason, it is felt by many to be a suitable measuring unit for judging whether an institution’s investment strategy has worked.

In this year’s Viewpoint we examine rolling 10-year returns since FY2009. They paint a picture that is far from clear. Most institutions seek to maintain the purchasing power of their endowments after investment returns, spending and fees in order to deliver a constant—and, ideally, constantly growing—level of support to the operating budget. But 10-year returns have consistently fallen below endowments’ long-term investment objectives—sometimes well below—even though the objectives have themselves been somewhat reduced. And while the robust investment results of the last seven years have boosted rolling 10-year returns, this year’s 2.4 percent average return has served to reverse that trend.

In this year’s Viewpoint we examine rolling 10-year returns since FY2009. They paint a picture that is far from clear. Most institutions seek to maintain the purchasing power of their endowments after investment returns, spending and fees in order to deliver a constant—and, ideally, constantly growing—level of support to the operating budget. But 10-year returns have consistently fallen below endowments’ long-term investment objectives—sometimes well below—even though the objectives have themselves been somewhat reduced. And while the robust investment results of the last seven years have boosted rolling 10-year returns, this year’s 2.4 percent average return has served to reverse that trend.

During this same seven-year period, universities’ spending from their endowments has remained generous. In the aftermath of the global financial crisis, spending as a percentage of assets has remained stable and, in dollar terms, for many institutions has grown substantially from year to year.

This mismatch between lower but still aggressive investment goals, lower long-term returns and a continuation of generous spending practices may bode ill for the ability of institutions to maintain the purchasing power of their endowments in a future environment in which economic growth and investment results may be subdued in comparison with recent years.

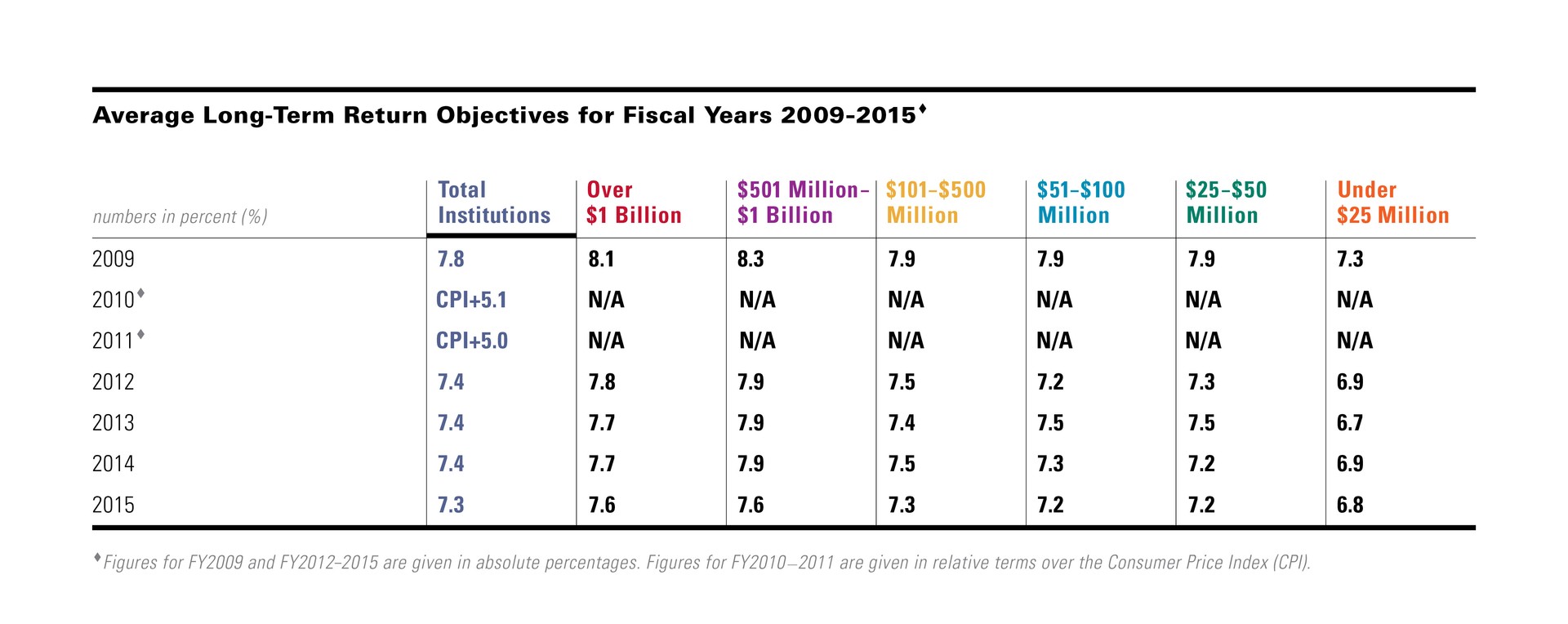

We begin with an examination of universities’ investment goals. The long-term investment goal, expressed as a percentage, is typically built up from historical expectations of 2–3 percent for inflation, to which are added 4–5 percent for spending and 1 percent for fees. Over the last seven years, institutions have reported long-term return objectives falling between 6.5 and 8.0 percent.¹

Larger endowments tend to have higher long-term investment goals than smaller endowments. Their confidence in setting these goals is due, among other things, to the greater average expertise of their investment committees, their higher degree of portfolio diversification, larger numbers of expert staff, access to top-performing managers and other institutional resources that tend to lead to higher investment performance. By comparison, smaller endowments’ long-term goals are generally 80 to 100 basis points (0.8 to 1.0 percentage point) lower than those of their larger peers.

It would be reasonable to assume that investment returns should bear some relationship to long-term return goals. But, although endowments on average reported double-digit returns each year from FY2010 until FY2014 (with the exception of the slight loss in FY2012), long-term return goals have been declining gradually among all groups since FY2009 and are now some 50 to 70 basis points lower than they were in that year.

If we look beyond the one-year return numbers, we can see that this decline in long-term goals may be due to the persistence of lower long-term returns. During most of the last seven fiscal years, reported 10-year returns have been well below the 7–8 percent long-term investment goals reported by the same institutions. In other words, even during the recovery period, endowments have failed to meet their own investment objectives.

Viewed in historical terms, the 10-year returns measured in both FY2009 and FY2010 encompassed not only the global financial crisis but also the negative returns that resulted from the bursting of the tech bubble in FY2001-2002. Ten-year returns for the largest institutions remained higher and recovered more quickly, but it was not until FY2012 that they rose above 7 percent. For the second- and third-largest size groups, 10-year returns only breached the 7 percent level in FY2013. None of the smaller three size cohorts has yet reported 10-year returns at or above 7 percent.

Perhaps more important, FY2015’s lower one-year returns have brought an end to the recovery in longer-term returns as well. From an overall average of 7.1 percent in FY2014, 10-year average returns for the total participant group sank 80 basis points, to 6.3 percent, in FY2015. This average was paralleled by declines in each size group ranging from 60 to 100 basis points.

If, as many economists believe, the next five years will be characterized by lower global growth and correspondingly lower investment returns than in the past, 10-year average returns may continue to decline.

What are the implications of this mismatch between goals and experience for the missions of institutions of higher education? One way to answer this question is to examine whether spending patterns have changed in the period under review.

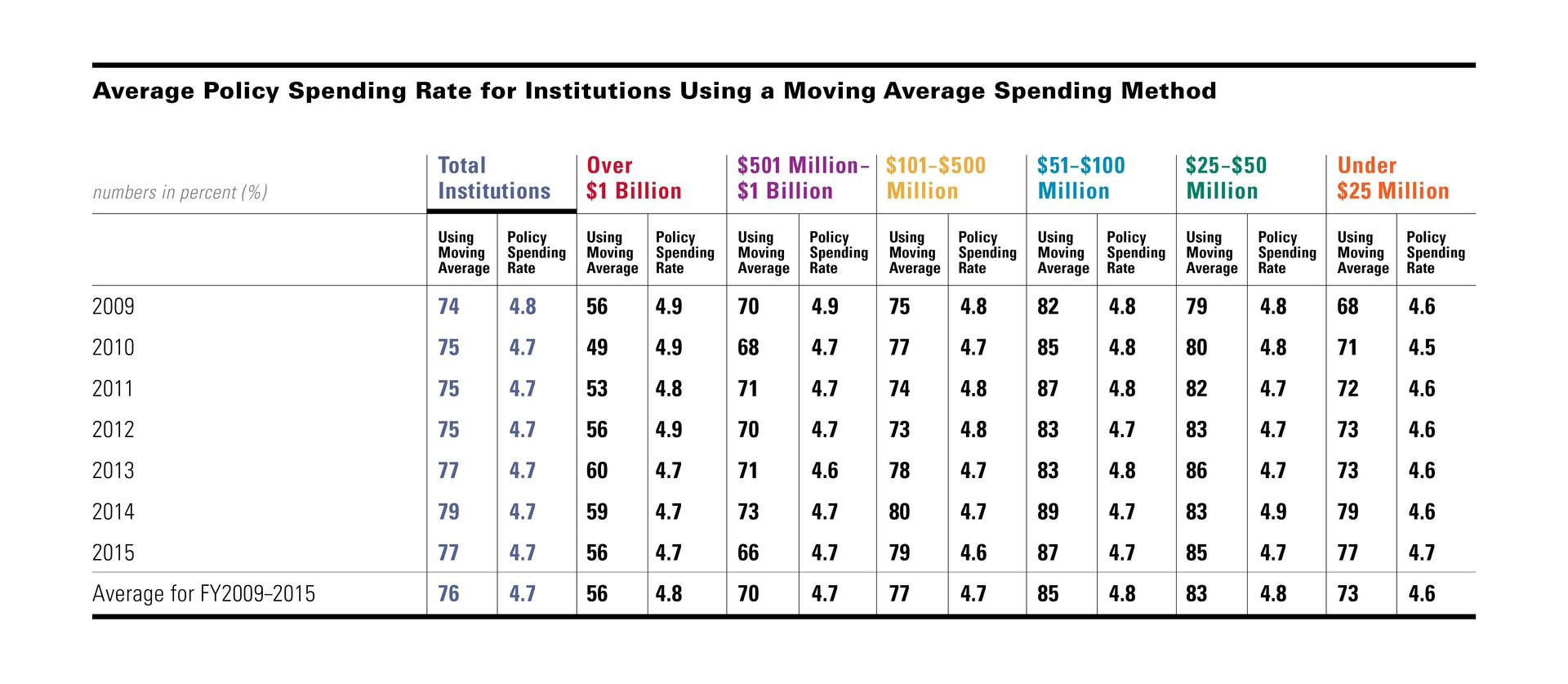

Investment returns vary from year to year, but most institutions seek to minimize volatility in the annual amount they draw from their endowments. Institutional budgeting practices, which often contemplate a multi-year horizon, also require a certain amount of stability for planning purposes. In addition, many larger institutions rely on their endowments for a significant proportion of their operating budgets. For these reasons, a clear—and, in some size groups, overwhelming—majority of institutions rely on a multi-year smoothing rule first proposed in the 1970s, pursuant to which spending is calculated by applying a percentage—the “policy rate”—to a figure calculated by taking the average market value of the endowment at the beginning of the preceding three years or twelve quarters.²

It is striking how stable this practice has remained over the last seven years. Among NCSE participants as a whole, use of the moving average method has been in the mid- to high 70 percent range during the entire period. Even among the largest, most endowment-dependent institutions, between 49 and 60 percent report using this method; among the other size cohorts, the moving average method is never used by less than two-thirds of the group, and usage is frequently above 80 percent.

Just as remarkable is the stability in the policy rate that is applied to the average endowment value. It has consistently remained between 4.5 and 4.9 percent across all size cohorts. While the rate has declined very slightly, by 10 to 20 basis points, over the last seven years, among the smallest cohort it has actually gone up by 10 basis points. On average, policy rates have remained between 4.6 percent and 4.8 percent since the crisis.

Thus, despite the fact that long-term investment returns have failed to meet long-term investment goals, spending rates and formulas have not changed materially and have, in fact, continued to be calculated in the same way.

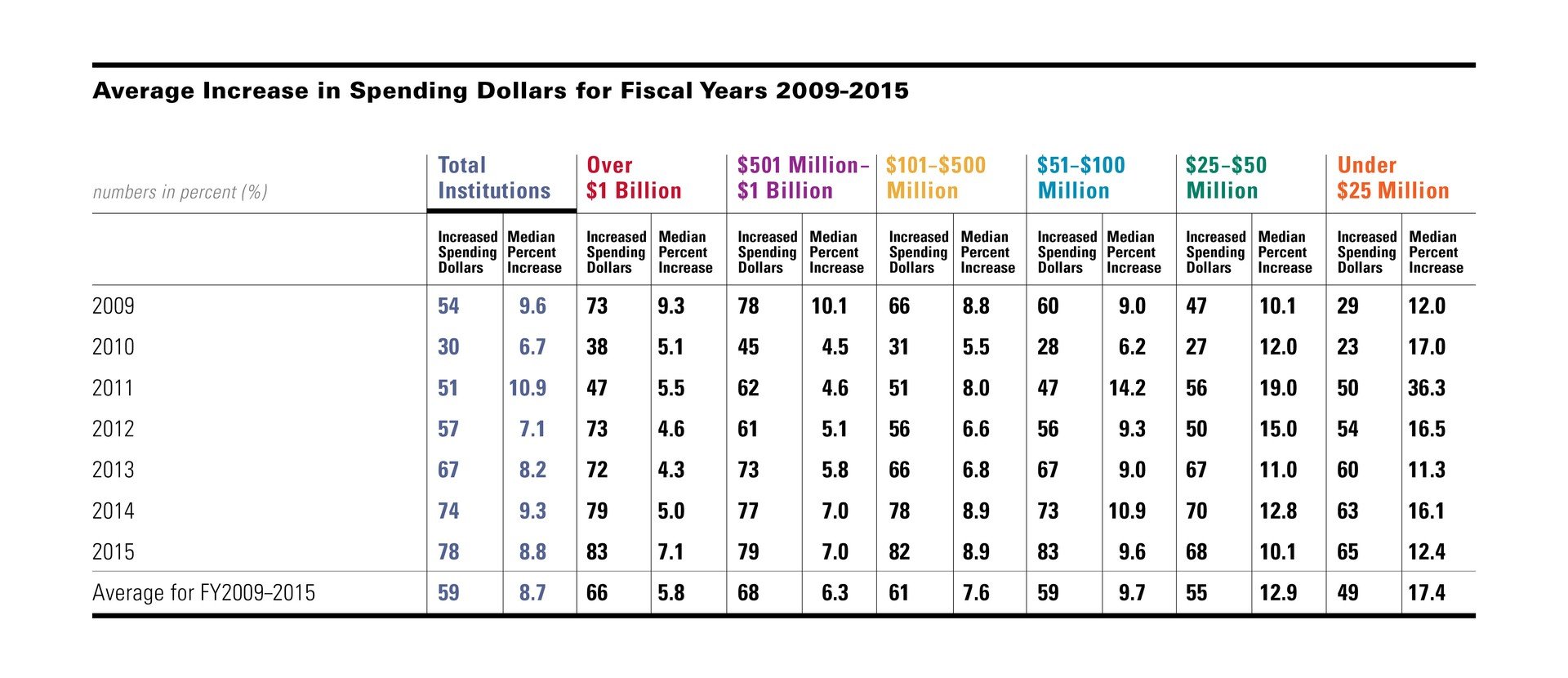

This circumstance can be seen more clearly in the proportion of participating institutions that increase their endowment spending in dollar terms from year to year. In every year except FY2010, an average of between 51 and 78 percent of institutions reported that they increased their endowment spending in dollar terms. Even in that post-catastrophe year, fully 30 percent of institutions increased their dollar spending, ranging from 23 percent of the hard-hit smallest institutions to 45 percent of those with endowment assets between $501 million and $1 billion.

Nor were these increases trivial. The lowest median increase for the group that raised dollar spending was 6.7 percent, again in FY2010, but the highest was the following year, when the group increased dollar spending by 10.9 percent. Over the seven-year period an average of 59 percent of institutions has increased dollar spending from year to year, and the average of the median increases has been 8.7 percent, well in excess of inflation.

Smaller endowments have increased their dollar spending at a higher percentage rate overall than larger ones. This should not be surprising, since the larger institutions began with higher dollar amounts and any increases, while substantial in dollar terms, would likely be smaller in percentage terms.

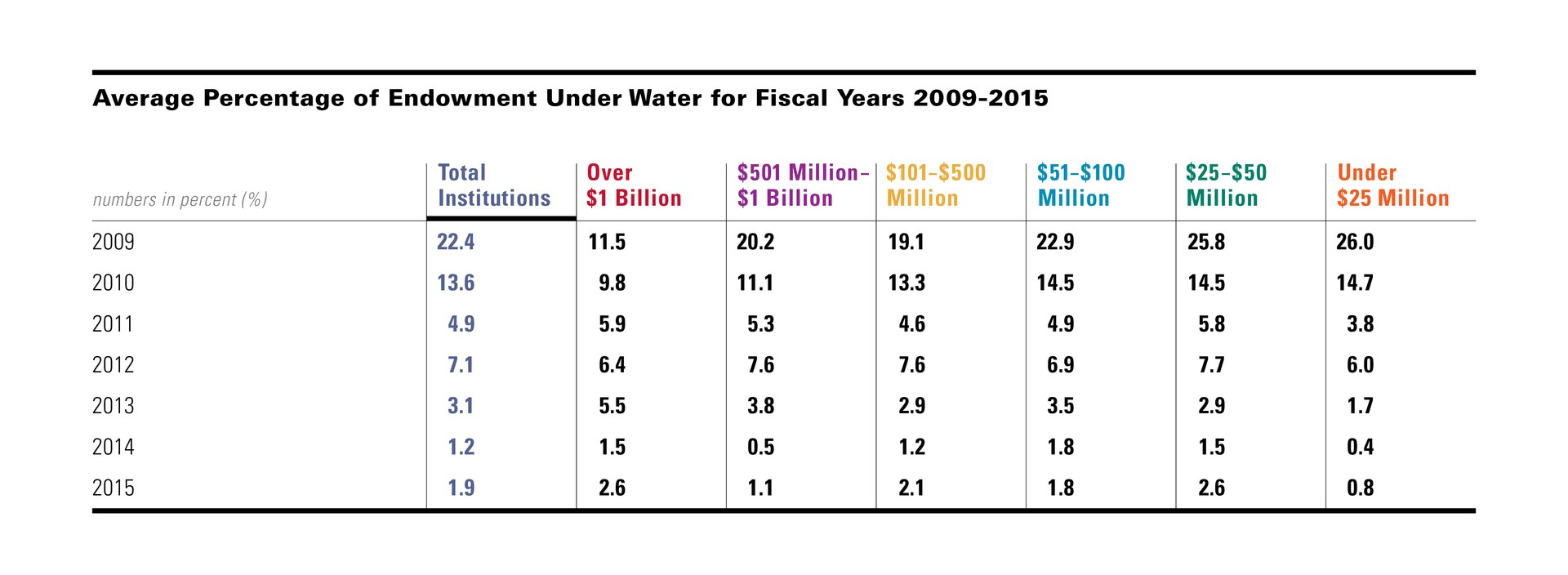

Increases in dollar spending were doubtless constrained, in the FY2009-2010 period, by the presence in many endowments of underwater funds—funds whose value had fallen below the “historic dollar value” that they had when created. Often relatively new, these funds lacked a cushion of accumulated but unspent gains and, in most states, the law that prevailed at the time prohibited or limited spending from such funds. It is in this light that the lower FY2010 incidence of higher dollar spending should be viewed. This dilemma was a spur to the enactment throughout the nation of the Uniform Prudent Management of Institutional Funds Act (UPMIFA), which had been proposed in 2006 but acquired new urgency as nonprofits of all types found themselves constrained by law from drawing on their endowments to support their missions.

We invest for the long term, but we live day to day. The fact that educational institutions have continued to sustain their spending rates and have—aided by a recovery in gifts and donations—increased their spending in dollar terms is laudable. But is it sustainable? If long-term returns continue to be lower than assumed by institutions’ long-term investment goals, and if spending continues at rates that are not supported by those returns, then the logical result will be a gradual erosion of purchasing power due to inflation and overspending. UPMIFA assumes that, over the long term, donors expect fiduciaries to maintain the purchasing power of their endowed gifts. If higher spending persists—or is demanded by new legislation—it is not difficult to imagine some donors deciding to make annual gifts rather than see their endowed gifts wither away.

The judgment of success or failure for any endowed perpetual institution lies, ultimately, in the balance between the success of its mission in the present age and its ability to conduct that same mission in the future. Financial resources are a key part of that mission. As the world economy enters a period in which growth may be subdued, the striking of an appropriate balance becomes more important than ever.

- In most years, we have asked NCSE participants to express their long-term investment goals as an absolute percentage. In FY2010 and 2011, we asked them to express their goals in terms of a margin over the Consumer Price Index (CPI). The two methods, as can be seen, yield essentially the same answer.

- Much less frequently, five years or twenty quarters may be used; other periods, such as seven or even ten years, are used by a small number of institutions.

This viewpoint appeared in the 2015 NACUBO-Commonfund Study of Endowments (NCSE) published February 2016.