It is hard to imagine that in the short span of less than 18 months, energy markets went from a state of overabundance to one of severe shortages and skyrocketing prices. In April 2020, Brent oil traded at its lowest levels since 2001 while the U.S.-based West Texas Intermediate settled at a negative price as tanks filled quickly and traders resorted to expensive storage alternatives.

Back then, the world faced an enormous drop in demand as manufacturing around the globe shuttered in response to COVID-19, while Saudi Arabia and Russia kept production high and engaged in a price war to gain market share. Today, the world appears to be on the verge of an energy crisis as production has not kept up with increasing demand. As the effects of COVID-19 begin to subside, factories are approaching full utilization capacity to meet demand, and the oversupply of natural gas and crude oil has quickly turned into supply deficits.

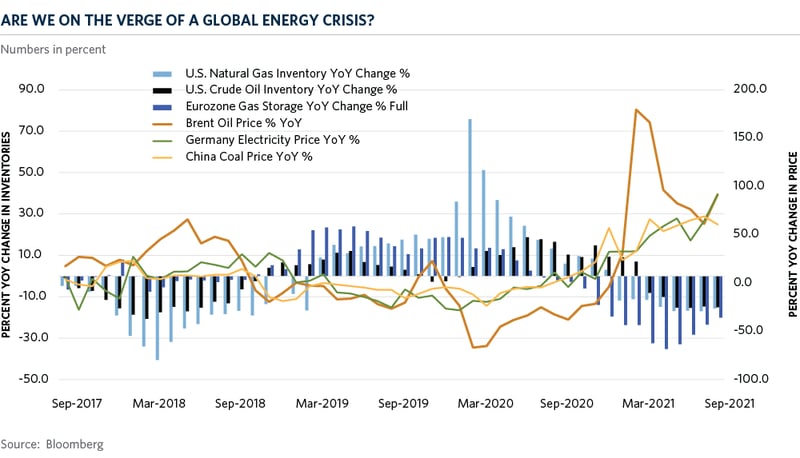

In this month’s chart, we show the year-over-year change in U.S. crude oil and natural gas inventories as well as the change in European gas storage (percent of full storage). Currently, available stocks are between 10 and 30 percent lower than last year, with some European nations experiencing a 60 percent drawdown.

In China, central government officials ordered the country’s top state-owned energy companies to secure supplies of oil, natural gas, and coal at all costs for the upcoming winter. As seen in the chart, China’s thermal coal prices are up over 60 percent versus last year. China’s power shortage could take a toll on its fourth quarter economic growth and trigger further fiscal policy easing in the near term. More than 20 provinces, accounting for more than 70 percent of GDP in the first half of 2021 have announced emergency power cuts so far. Furthermore, the goals of maintaining strong economic growth and achieving peak power sector emissions before 2030, and carbon neutrality by 2060, could exacerbate the current situation. India is also experiencing a power crunch as coal inventories have declined to dangerously low levels.

In Europe, natural gas prices have skyrocketed along with electricity prices and the offsetting carbon credits. Electricity prices have risen between 50 and 300 percent in different parts of the Eurozone while current natural gas on hand is 20 percent lower compared to last year. Natural gas prices in the U.K. and the Netherlands are close to six times higher than last year, partially due to Europe’s continued efforts to remove coal-fired power plants from the grid and replace them with less carbon intensive resources. A weather-driven drop in wind-generated power has coincided with a colder-than-expected September amid the lower supplies of natural gas, further straining the system.

On the supply side, deliveries from gas producing countries like Norway and Russia have been slow into Europe despite the more attractive price levels. Some have speculated that the surprising lack of supplies from Russia, the leading gas exporter to the Eurozone, is an attempt by Russia to capitalize on the current energy crisis to bolster the case in favor of the Nord Stream 2 project supplying gas into Germany through a pipeline under the Baltic Sea. The project has been heavily criticized as continuing Europe’s dependence on fossil fuels and strengthening President Putin’s position in geopolitical relations. In the U.K., a slightly different version of energy shortage is occurring, affecting mostly drivers. A scarcity of truck drivers due to foreigners leaving the country post-Brexit has resulted in 30 percent of the 1,200 gas stations being left without fuel. In response, the British Army mobilized 200 military personnel, including 100 drivers, to deliver fuel across the country.

These developments in the energy sector are supporting the case for higher levels of inflation for longer. As global economies continue to recover from the pandemic, while simultaneously moving towards reducing carbon emissions, it is resulting in an energy crunch. Investors and institutions are shying away from the energy sector at the same time that producers are reluctant to increase capital spending, leading to declines in production and persistently high energy prices. The world could be about to enter a cold (and expensive) winter.