The potential for rising inflation is becoming a top concern for many investors and consumers. Many believe that inflation is already here as evidenced by price increases in commodities, homes, shipping rates and used vehicles. Following a year of unprecedented monetary accommodation and fiscal support, markets are rightfully nervous as COVID-19 vaccination rates improve, sparking optimism about pent-up demand growth which would put more pressure on supply chains that are already strained. Among all the factors driving inflation rates, central bank liquidity creation is often cited as critical.

As a result, it is reasonable to ask whether the Fed’s massive stimulus during the pandemic might affect inflation. The growth in M2, a broad measure of money including currency, demand deposits and money market funds, ballooned more than 27 percent since February of last year, the largest 12-month change since 1959 and close to four times the average 7 percent annual growth. In this month’s chart, we show that inflation has exhibited no relationship to broad money growth historically.

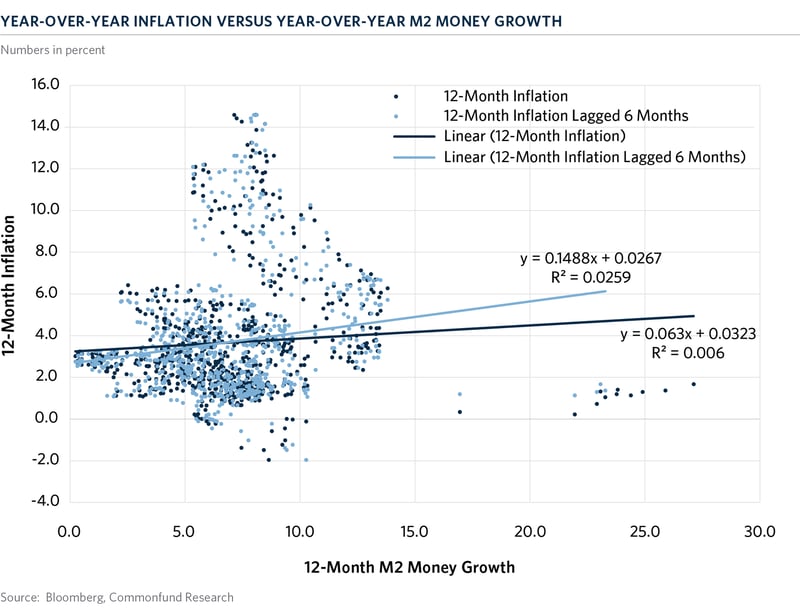

The chart depicts 734 monthly observations of 12-month growth in M2 money supply on the X-axis and the corresponding 12-month inflation rate on the Y-axis. Perhaps surprisingly, both the dotted trendline in dark-blue and the R-squared coefficient, which measures the proportion of inflation rate volatility explained by the change in M2 growth, are close to zero. We also looked at these measures on a lagged basis to account for the possibility that it takes time for money growth to impact inflation. Again, the data shows no relationship between the growth in M2 and the 6-month lagged inflation, as shown by the light blue trendline.

For excess liquidity to create inflation, it needs to lead to a sustained increase in spending and loan growth. So far, bank lending has been anemic while the global velocity of money and the money multiplier (the ratio of broad money to base money) has fallen more than during the Great Financial Crisis. Given the rapid increase in vaccinations in the U.S., the expectations for spending recovery may lead to an improvement in demand for credit and banks’ subsequent willingness to lend. If that proves to be true, we believe that loan growth will depend more on economic outlook optimism, rather than the level of deposits banks hold. In addition, excess savings, which have been built over the last 12 months, may dampen demand for credit or be used pay down debt. At Commonfund, we believe that while supply disruptions, elevated commodity prices and base effects could result in higher 12-month inflation rates, these effects will be temporary and unwind once the bottlenecks are removed. In addition, we believe that the secular trends of automation and robotization, declining labor force participation, aging population and high debt levels will continue to suppress inflation over the long-term.