At Commonfund, we aim to build multi-manager, active risk equity portfolios with a clear objective of consistent outperformance versus passive policy benchmarks. Our approach is to take intentional and measured “risk away from the benchmark” by allocating to a variety of managers who employ active risk strategies that are uncorrelated to one another. We view the investment universe through a risk factor lens and have the quantitative capabilities and machine learning techniques to measure the various risks existing managers bring and potential managers might bring to our portfolios. Under our microscope, we disentangle, map and tally “risk away from the benchmark” quite specifically to known risks such as: market risk (i.e., simple beta exposure), regional risk (relative country bets) factor risks (like value or growth), sector risks (like healthcare or financials) and idiosyncratic risk (security specific risk that is difficult to attribute to the aforementioned). We do this at the underlying manager level and then at the aggregate multi-manager portfolio level.

Big Deal! So what? Well, we think it’s a big deal because we prefer some risk types to others and this factor lens gives us the ability to differentiate and, thus, build “intentional” active risk equity portfolios. For instance, we value idiosyncratic risk highly as it provides significant diversification value and alpha potential. Conversely, we seek to control and limit risk factor exposures that can bubble up across stock portfolios and create risk redundancies if left unchecked. Furthermore, we seek out and build into our portfolios non-traditional risk factor premiums that do not typically occur in traditional stock picking portfolios: these also offer diversification value in addition to potentially uncorrelated excess return sources. Finally, we risk weight our allocations across managers such that no single allocation (or cross-manager redundant risk factor) should drive total portfolio excess return over any reasonable length of time.

Why do we pay such close attention to factor risks? We do so because factor exposures have the potential for unpredictable and significant market moves that can quickly offset hard fought alpha production. Let’s consider value and growth factors and explore the ramifications of an investor being over / under exposed to one or the other as an active risk source over the last 12 months and over time more generally.

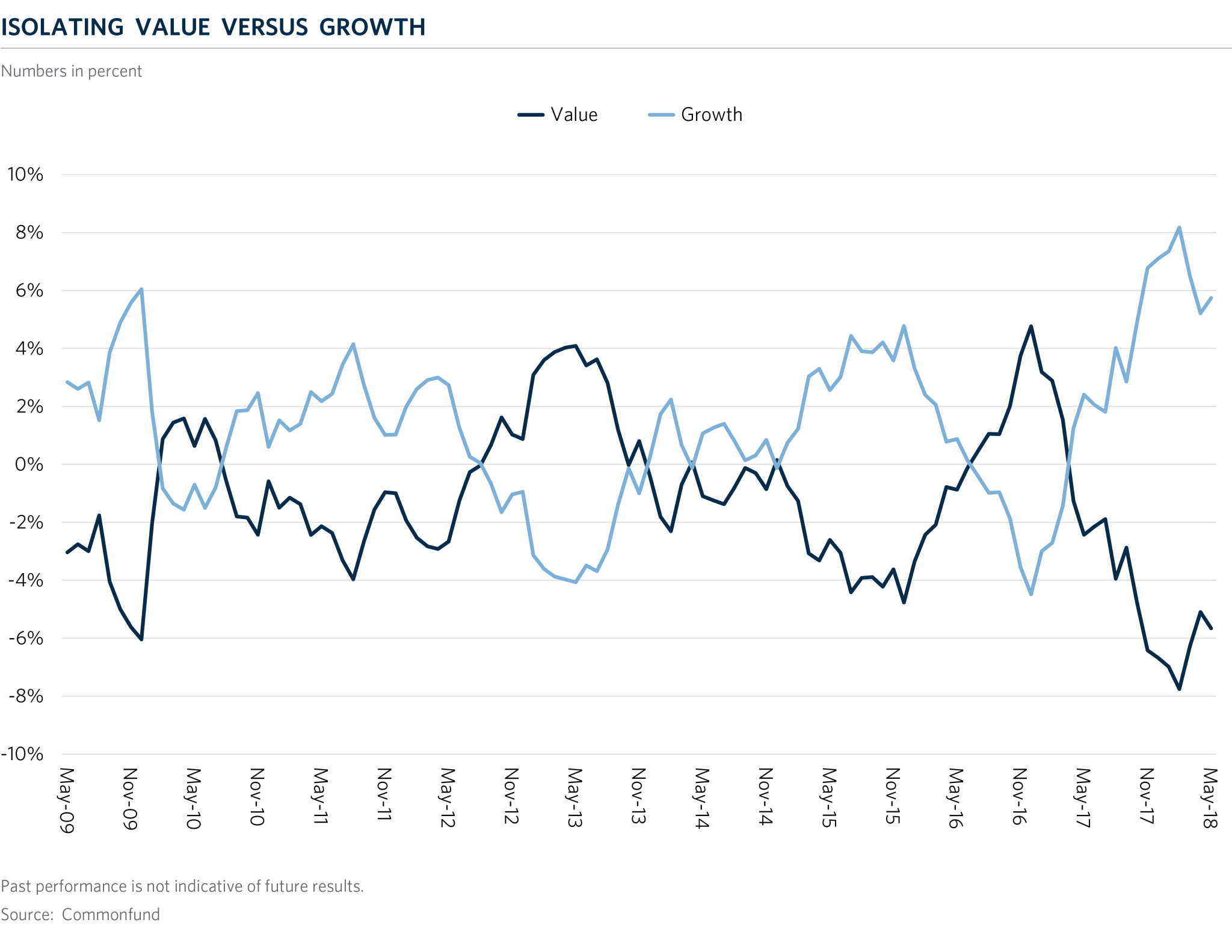

The following chart shows rolling 12 month returns of the Russell 1000 Growth Index minus the Russell 1000 and the Russell 1000 Value Index minus the Russell 1000, isolating the growth and value factors in large cap U.S. equities over time. Over the 12 months ending February 28, an allocation to growth was worth 8% more and to value 8% less than a simple allocation across the diversified index. Great news if your institution had intentionally (or unintentionally, for that matter) chosen a growth bias and awful news if the opposite. In either case, it’s difficult to know when to reverse the trade. Looking back further over time, one sees significant variation and directionality across both of these factors. Our research, and indeed the research of many other market participants, has shown that investors do not generally demonstrate repeatable edge in factor timing. Therefore, we aim to measure, limit and diversify the amount of active risk return variation our portfolios experience directly from factor exposures.

In a competitive active equity management landscape, where 100 basis points a year over a benchmark puts you amongst the top quartile of a peer group, every basis point counts. Recognizing this, 800 basis points of risk away from the benchmark resulting from a factor bet where significant edge is not apparent represents a risk we aim to limit.

The intended outcome of allocating risk in such a measured and controlled manner is that the volatility of our active return versus the benchmark should be fairly tight and the sources of that volatility will be readily identifiable. Furthermore, a greater percentage of our excess return should be driven by the idiosyncratic risks our managers bring to the portfolio, where we believe they possess explainable “edge” in their approach and thus also a greater chance of repeatable success, rather than from factor exposures whose predictability of returns are more capricious.