Currency risk can best be described as the surprise impact that currency exposure has on an investment portfolio. Although currency risk typically confounds investors, it is easy to measure – it is the difference in the return to an unhedged portfolio position versus that portfolio position hedged back to the investor’s domestic currency. So simple to measure, yet so difficult to figure out.

Currency risk has long bedeviled investors, with many opinions and recommendations as to whether investors should even hedge their currency exposure. Unfortunately, there is no easy answer and the debate over the best currency strategy continues. Some take the view that, over the long term, currency fluctuations will average out. Another school of thought is to actively manage your currency hedging ratio by determining the hedge ratio that minimizes portfolio volatility. Finally, others argue that if there is no risk premium associated with currency exposure, and investors are not therefore compensated for the volatility that it introduces into the investment portfolio, then the currency should be completely hedged.

Taking a step back, currency risk is fascinating because it is a by-product of international investing. Currency has no long-term expected return because, although it is a risk exposure, it is not an economic asset for which a long-term risk premium exists. Investors do not invest in currencies to capture a risk premium; instead, they invest in international assets denominated in a foreign currency. As a result, investors received currency exposure as a side effect of their internationally diversified investment portfolios.

Another way to think about currency is that it has no intrinsic or standalone value by itself. For example, we can assess whether the stock market is over or undervalued by using fundamental economic data embedded in the equity market. Corporate earnings, profit margins, P/E multiples, dividend yields and the like can all be measured and assessed to determine if the stock market is rich or cheap.

Not so with currencies. We cannot say whether the US Dollar is overvalued or undervalued on a standalone basis. We can only make this determination relative to another currency. For example, we can say that the USD is expensive compared to the Euro or cheap compared to the British Pound. Currencies are not an asset class and there is no long-term risk premium to capture. Instead, they are merely a relative trade compared to another currency.

Yet, why do investors believe that currencies are an assets class? The reason is that currency strength or weakness compared to other currencies tends to be episodic. The USD is currently strong relative to the Yen, the Euro, and the Remimbi. This is because each of these countries or economic regions is suffering from significant economic headwinds and they have all devalued their currency to stimulate their export industry. It is expected that the Central Banks of these regions will continue to lower the value of the Yen/Euro/Remimbi relative to the USD to stimulate export growth, and this might go for years. As a result, the USD begins to look like a valuable asset class. Unfortunately, there is no long term risk premium for the USD that would allow us to build any reasonable return expectation—the strength of the USD relative to other currencies is at the whim of central banks.

Which brings us to another topic. There are few certainties in the investment world but here is one: If you hedge your international currency exposure, at some point, you will lose money. I cannot tell you when, but currency fluctuations are large and extreme and will eventually cause your currency hedge to lose money.

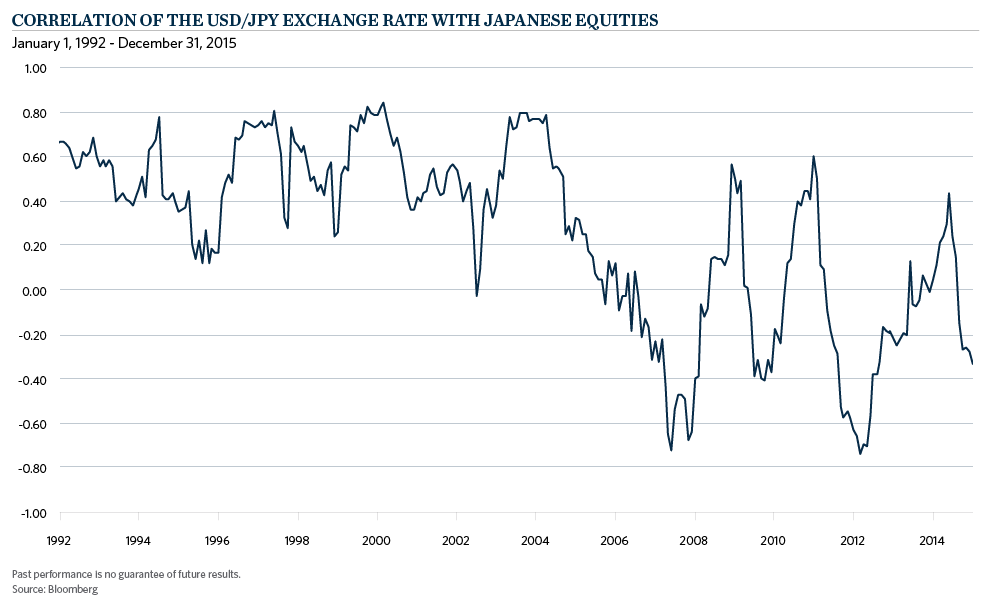

Consider the chart below which measures the correlation of the USD/Yen and underlying local stock market. We can observe large, dramatic swings in the currency value relative to the local equity market. For example, the correlation between the USD/Yen exchange rate and the Nikkei stock market ranges from + 0.80 to -0.80. This large dispersion indicates that there were times when it was advantageous to hedge the Yen and times when hedging the Yen resulted in a loss. Predicting currency strength or weakness is not easy. As the chart demonstrates, the relative strength of a currency can turn quickly based on a whole host of competing monetary and fiscal policies across international borders.

Yet, some currency traders make money don’t they? Yes, they do. But they don’t seek to capture a long term risk premium the way you would through normal portfolio construction. Instead, they monitor central bank movements and government fiscal policies to jump on or off a currency bandwagon when they see fit. For them, currency is not an investment associated with an asset class: it is a trade.

Yet, some currency traders make money don’t they? Yes, they do. But they don’t seek to capture a long term risk premium the way you would through normal portfolio construction. Instead, they monitor central bank movements and government fiscal policies to jump on or off a currency bandwagon when they see fit. For them, currency is not an investment associated with an asset class: it is a trade.

At Commonfund, we monitor currency movements to determine if there is a tactical advantage to hedging or being “long” a currency. We are mindful that some currencies are simply too volatile to make effective tactical calls. However, we are well aware of the “race to the bottom” with respect to other central banks reducing the value of their currency relative to the USD to enhance exports and we use this knowledge to look for opportunities to enhance our portfolios.

So where does this leave us? Unfortunately, back where we started—there is no easy answer to currency exposure. But, consider this: ask yourself the reason for putting on the currency trade in the first place. If it is for risk reducing purposes, then put aside the behavioral emotion of regret and recognize that at some point you will lose money on your currency hedge. This is OK because you are not trying to earn a risk premium from currency. Instead, just like trying to eject an unwanted relative from your home after the Holidays, you are trying to eject an unwanted risk exposure from your portfolio.