Few topics get investors’ attention as much as fees. We wouldn’t be human if we all didn’t want to know, in detail, how much something costs. In the world of investing, fees are an even more important topic, as they directly relate to your investment performance. To state the obvious, the more you pay in fees, the less you make in return. When investing in equity managers, fees paid are critically important because a large component in the “active vs. passive” debate is the ability of active managers to outperform, after fees (emphasis added). Our approach is to attempt to tilt the odds in our favor, by lowering to the greatest extent possible the fixed fees payable to active managers. Our recent movement toward performance-based fees have helped in this regard.

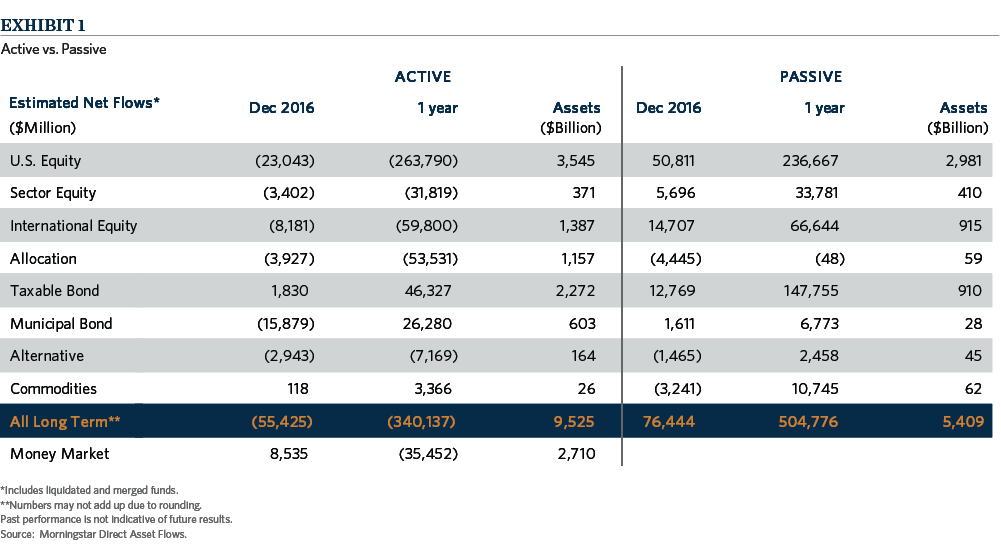

Any discussion about fees requires some perspective on the state of the active equity manager universe. It has been customary in our business for decades to “pay for talent”. Equity managers with strong historical performance and capacity constraints held a lot of the bargaining power in a fee negotiation, because if one investor didn’t want to pay the fee, another would gladly sign up. However, investor flows have severely impacted most active equity managers in the past 5-10 years, with some of the biggest contributors being the decline in the defined benefit pension market, the strong preference for passive products, and the proliferation of smart beta investment products. Exhibit 1 shows the dramatic flows out of active and into passive investments by strategy in the most recent calendar year.

The advent of smart beta, not only as a source of fund flows away from active, but also as it relates to the definition of alpha, has substantially changed the bargaining power of buyers of equities during a fee negotiation as well. Historically speaking, excess return over a benchmark was considered alpha, and investors were willing to pay for positive excess return. Today, sophisticated statistical techniques can be used to identify “true” alpha (idiosyncratic return not explainable by betas). True alpha can be defined as excess return after accounting for factor variables such as value, momentum, size, quality, etc. Each of these factors has in some form or another been a source of historical active management excess return in the past, and can now be accessed individually through smart beta passive vehicles, such as ETF’s, that operate in direct competition with active managers. Thinking of these factors as “passively replicated exposures” forces buyers to think of active management, and the associated fees in a different context. It only makes sense for active management fees to come down to account for the increased competition for investors’ dollars. Our experience has been that managers are acutely aware of the changing landscape and we have used that shifting bargaining power to our advantage whenever possible.

Over the course of the past several months we have renegotiated a number of fee arrangements with managers, with the goal of decreasing the flat fees paid to give investors a greater chance of winning. Where appropriate, we have negotiated performance fee arrangements so that our interests are aligned with our managers. We strive to pay for outperformance, or alpha, and pay nothing, or close to nothing, for market returns, or beta, whichever form it takes. Under this approach, managers that outperform will be paid an incentive fee, better aligning interests. In addition, in arrangements where we have minimal or no flat management fees, we pay nothing for underperformance. In some instances, we have capped the amount of incentive we are willing to pay in order to reward consistency and not compensate for excessive risk taking.