These industries may seem an odd pairing, but both are in the midst of a disruption-led, industry-wide rationalization process. The two industries share in common a historically evolved “bundling” price structure, heavily favoring the sellers, that is breaking down due to the recent proliferation of distribution alternatives. This is giving consumers the option to be far more choosey about the prices they are willing to pay for varying levels of content.

Bundling

Bundling is a pricing technique that allows sellers to group together different combinations of products for customers who, often happily, purchase the pre-arranged package in exchange for the convenience of one-stop shopping. It can be a win-win situation for both producer and consumer.

Bundling works less well when the package in total, relative to the sum of its parts, is perceived to be too expensive or when consumers no longer believe they are getting a fair proportion of what might be perceived as the “good stuff”. Greater transparency into component costs and consumers' increasing options for a la carte purchases of both television entertainment and investment product is putting pressure on industry pricing standards, and particular pressure on providers whose value propositions are not so easily differentiated.

Cutting the Cord

It's not news that “cable cord cutters” are growing in number each year as other means for viewing programming cable companies used to distribute exclusively is now available through myriad alternative providers – Netflix, Hulu, HBO Go, etc. Why pay $200 a month for a premium cable package when you really only want to watch HBO, which you can now buy as a standalone for $15 a month? Every cable customer understands the implications of bundling, and, indeed, many have begun to de-bundle, as they isolate and pay for only the programming they really want.

Somewhat less obvious, standard hedge fund pricing also resembles a “bundled” structure. In the case of hedge funds, it is various betas, or readily accessible risk factors, that are being sold in combination with varying amounts of “alpha”, or truly differentiated return streams. The betas, which are prevalent, on their own would be priced relatively inexpensively; the alphas, scarce and sought after, should command higher prices. An ever-growing array of ETF's and factor replication products, combined with increasing sophistication levels of hedge fund consumers, has resulted in many now refusing to pay hefty fees for beta and factor exposures they might access at far cheaper cost.

The difference between hedge fund providers who are producing mostly alphas versus betas is perhaps less transparent to the casual observer than the difference between really compelling television programming and mediocre production, but it is discernible with the right analysis. At Commonfund, we have the quantitative tools to decompose any managers' returns, hedge fund or otherwise, into their underlying risk factors and are thus keenly aware of whether a particular manager is truly delivering legitimate, uncorrelated alpha or simply repackaged beta. We are willing to pay up for the alpha; we are incredibly frugal when it comes to paying for beta.

Running the Numbers

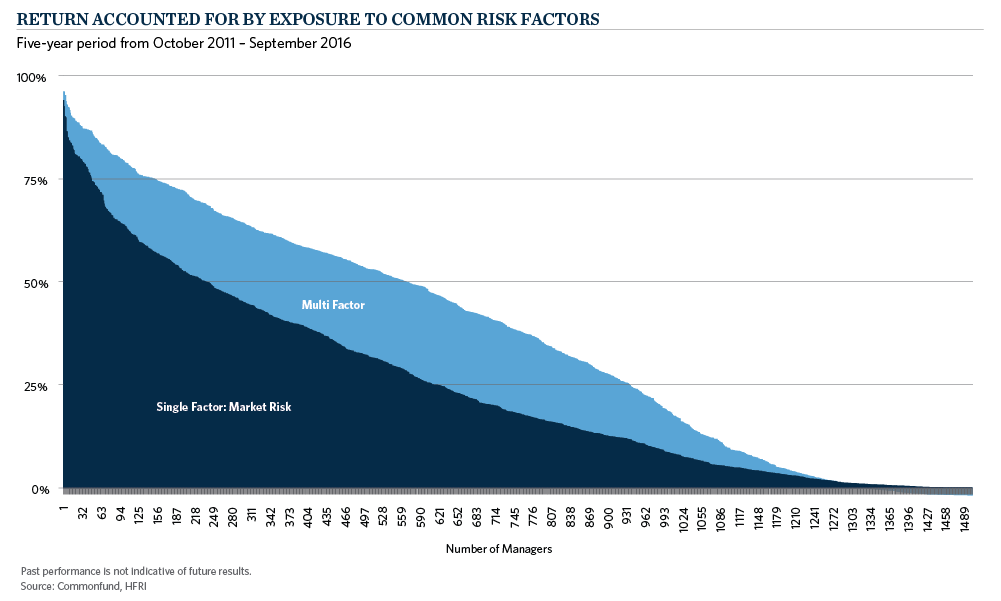

To illustrate the point, we ran a quick diagnostic on the 1,489 Equity Hedge, Macro, Relative Value and Event Driven funds in the HFRI database that have more than $100 million in AUM and a track record of 5 years or more. On average, these funds are charging a 1.05% management fee and 16% incentive fees. The chart below shows the results of “fitting” these managers' returns to a single risk factor – namely, the equity market – and then to a group of off-the-shelf risk factors that any institutional investor might purchase more economically. For 200 managers in the sample, the equity market alone explains about 50% of the managers' returns. For 550 managers in the sample, a combination of readily accessible risk factors describes a similar 50%. As you move from left to right in this chart, the proportion of (desired) alpha to (commoditized) beta grows. Unsurprisingly, we focus our research on the right tail of these managers.

Content is King

Hit shows and the companies that produce them will continue to be rewarded for the discernible value they produce. In fact, just last year, DreamWorks Animation, Miramax and Legendary Entertainment were all acquired at significant premiums in an industry consolidation rewarding content creators. Similarly, hedge funds who are able to generate compelling content, which we might call “alpha”, will be able to continue to demand premium pricing, and investors will be willing to pay up for this content. The future will be less rosy, however, for hedge funds, or traditional long only managers for that matter, who are unable to produce truly value-added return streams.

Implications for Hedge Fund Investing

When you view the hedge fund universe through our lens – one that demands true alpha production – and are disciplined about not overpaying for beta, much of the investable hedge fund universe falls away. Equally and opposite, our lens helps to shine bright lights on producers of highly compelling and differentiated return streams.

So back to the title question of this blog – what do the cable television and hedge fund industries have in common? Perhaps most importantly, there continues to be premium content creation coming out of both. However, the savvy consumer might be better economically served by demanding a bit of “de-bundling” as he/she seeks to isolate the premium content they desire.

Hedge funds in general have had a very tough run of it in the press and in investor perception for a number of years. Indeed, some of this criticism is justified. Equally important, however, in our quest to build the most diversified and potentially value-added portfolios, is the recognition that there are extremely valuable producers of alpha streams, or premium content, scattered about the hedge fund industry. We are working very hard to find them.