When we look for potential roadblocks that could spoil the breakneck pace of capital markets, the first risk that comes to mind is record-high valuations. While inflation risks have become more top-of-mind recently, price multiples have been trending above historical averages during the last six years, except for a few brief periods of market correction. The U.S. is by far the most overvalued region with price-to-earnings and price-to-sales ratios 1.5 and 2 standard deviations above their mean values, helped by strong growth, capital inflows, supportive Fed policy and high allocations to expensive technology and consumer discretionary stocks.

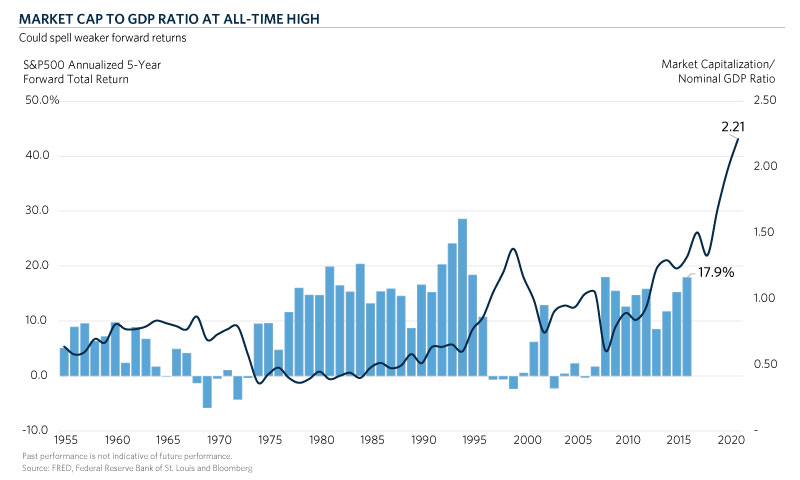

The Buffett indicator, the ratio of total market capitalization to nominal GDP, is another approach to measuring market valuation popularized by the famed Investor, Warren Buffet. The current estimate of the total U.S. market capitalization using the Wilshire 5000 index is around $52 trillion. Prior to 1970, the changes in the Financial Account - Nonfinancial corporate business; corporate equities; liability, Level were used to calculate the U.S. total market capitalization and complete the data series back to 1950. The ratio of the total market capitalization and the nominal GDP of $23.6 trillion yields a current Buffett indicator reading of 2.21, a record high since 1950. While no valuation indicator has been perfect at predicting future market performance, high levels in the ratio have been linked to lower returns in the following 5-year periods, specifically during the late 1960s, 1990s and mid-2000s.

Perhaps one of the biggest criticisms of the Buffett indicator and other price multiples such as the cyclically adjusted price-to-earnings (CAPE) ratio is that they fail to account for the level of interest rates. Investors decide on constructing portfolios around equities, bonds, hedge funds and real assets based on their investment return objectives and the relative return and risk properties of the asset classes. The steady decline in interest rates has produced strong gains for Treasuries over the past 30 years while eroding their future ability to diversify portfolios during risk-off periods. During the 1960s, 1990s and mid-2000s, investors had the option to allocate away from expensive equities to bonds with attractive yields. Today, allocations into Treasuries are expected to generate losses for investors after inflation, forcing them to seek yield and return in riskier assets. As a result, while markets are overvalued relative to their histories, they are fairly-valued relative to bond yields and are less likely to collapse as they did in 2000.

At Commonfund, we review close to 40 different indicators which inform us on the current economic environment as well as the attractiveness of risky vs. defensive assets. One of the indicators we follow closely is the equity risk premium which measures the earnings yield of regional stocks markets vs. Treasury and corporate bonds yields. And, while the U.S. remains the least attractive market from a valuation perspective, equities remain attractive relative to fixed income providing at least some support going forward.