Facing cost pressures and a new regulatory regime, healthcare organizations — especially those in the small and mid-sized range — should consider adopting the principles of the endowment model.

Nonprofit healthcare organizations are confronting an unprecedented series of challenges as they strive to maintain positive operating margins in the face of declining reimbursements from insurance companies and government payers. The crisis is particularly acute at smaller and mid-sized organizations. Having played a major role in their communities for decades, they are finding that the healthcare business model is changing. Medical practice models are being upended as many doctors are closing their independent clinical practices and becoming hospital employees in response to decreasing reimbursement levels and ever-greater demands for capital investment. In hospitals and clinics, the old-style model of bricks-and-mortar buildings located in major urban centers is being challenged by new delivery systems such as suburban mall-style “big box” shell structures with flexible wards that can easily be changed in response to the advent of new equipment and practices, free from the strictures of plaster walls and concrete slabs.

Although these challenges are being intensified by the regulatory and payment changes mandated by the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, they are not new. In fact, healthcare organizations have worked for years to cut costs and maximize operating efficiencies. Larger organizations and networks, with substantial endowments to support their operations, have been better prepared financially to adapt to the more stringent demands of the coming environment and have been more successful in reducing costs and tightening their organizational structure. Small and mid-sized healthcare providers, however, lack the economies of scale necessary to achieve meaningful cost reduction. For them, the way forward may include merging or affiliating with other organizations to form more competitive networks. With or without these operational steps, it will be essential that small and mid-sized healthcare organizations strengthen their resource base by improving their endowment management skills (and strengthening their ability to attract gifts and donations).

This article suggests that healthcare organizations must consider adopting the endowment management model that has been developed over the last three decades by educational institutions and increasingly copied by other types of nonprofits. The fact that it will take healthcare organizations several years to implement these changes and begin to reap their benefits makes this task all the more urgent.

The Margin Squeeze

Nonprofit healthcare organizations commonly operate with razor thin margins, or even at a deficit. Every day they provide crucial services to patients and the larger community, for which they incur substantial operating costs. To offset this expense, they seek to obtain revenue from three major sources.

- Reimbursement from federal, state, and local governments—by far, the largest income source for healthcare providers.

- Income from private insurers and self-pay patients.

- Finally, and at a considerably lower level, is support from donations or transfers from any endowment that the organization may have.

The conclusion is inescapable: Healthcare organizations will become more reliant on their endowments.

The excess, if any, of the first two categories of revenue over costs is the operating margin. An analysis of operating margins in the healthcare industry shows how thin the line is that divides surplus from loss. The 2012 Commonfund Benchmarks Study® Healthcare Organizations Report—a nationwide survey of 86 nonprofit healthcare organizations—reported a median operating margin in FY2011 of 4.1 percent. This figure was unchanged from FY2010 and just 0.1 percent lower than FY2009’s 4.2 percent, but much higher than the 2.9 percent reported in fy2008, which seems to have marked the low point from which healthcare organizations have been able to recover somewhat.

Constraints Faced by Healthcare Endowments

The world of healthcare organizations is thus increasingly being shaped by pressures affecting both the revenue and expense sides of the income statement. On the revenue side, these pressures take the form of tighter standards for government and insurance reimbursements. On the expense side, healthcare organizations have already carried out cost-cutting steps but it is clear that the larger organizations are positioned to realize far greater savings. In this environment, the conclusion seems inescapable that there will be greater reliance by these organizations on the third revenue source, endowment, to enhance surpluses and make up for losses.

Enhancing returns from endowment will, however, not be a simple task. Most health systems make use of bond issues to fund brick-and-mortar construction projects and other improvements. A successful bond offering depends in large part on the ability of the bonds to earn a high rating from the bond rating agencies, which look not only to the ability of the healthcare provider to generate cash flow but also to the liquidity of its endowment’s financial assets as a potential backstop source of repayment. Indeed, liquidity measures have come to form a key metric in determining bond ratings.

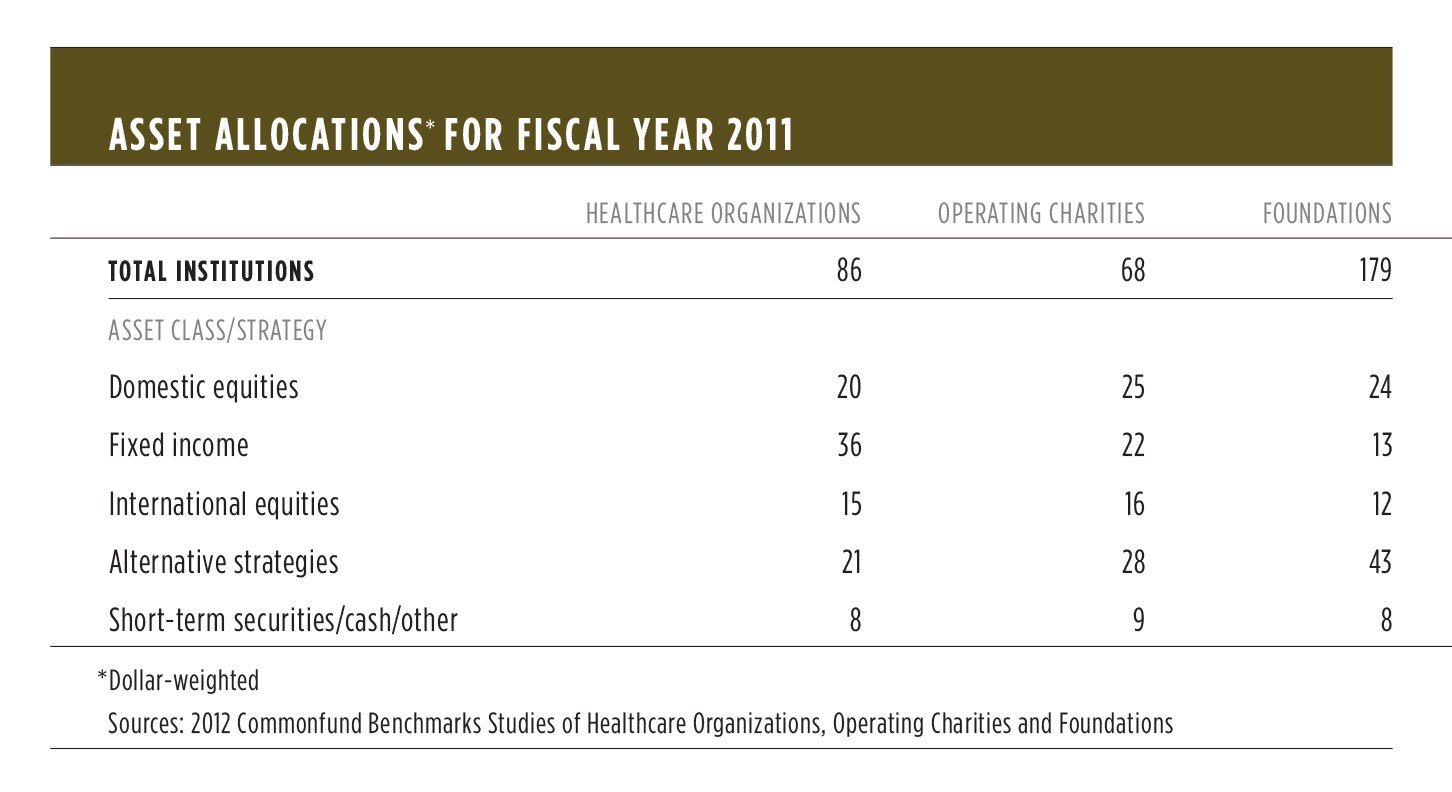

For this reason, the asset allocations of healthcare endowments have tended, on average, to be more heavily weighted toward cash and fixed income investments than those of other types of nonprofits. The table above compares healthcare organizations’ dollar-weighted asset allocations to those of foundations and operating charities as of December 31, 2011, as reported in Commonfund Benchmarks Studies for the relevant sector (direct comparison with educational institutions is not possible due to their June 30 fiscal year end).

As the table shows, the major differences among the three types of endowment lie in the allocations to fixed income investments and alternative strategies. Healthcare organizations and foundations are at opposite ends of the spectrum with respect to these allocations, while operating charities (cultural, religious and social service organizations) occupy the middle ground. The liquidity required by rating agencies accounts for a good measure of healthcare organizations’ high allocation to fixed income securities and their correspondingly low allocation to the relatively illiquid group of alternative strategies.

Yet this preference comes at a cost. It has long been accepted by investment professionals that asset allocation decisions account for the vast majority of the variation in an investor’s portfolio returns. The original, and still authoritative, studies on the subject found that 91.5 percent of the variation in returns could be explained by asset allocation policy choices as opposed to other types of activity such as security selection or market timing.

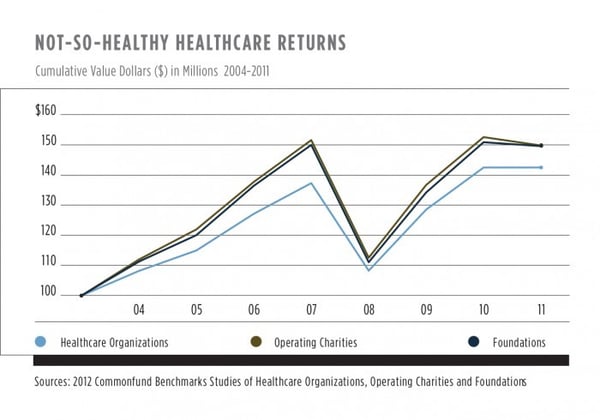

As a consequence of their bias away from the traditional equity orientation favored by other types of nonprofits, healthcare endowments have generally returned less per year than other nonprofits—a heavy burden to bear, and one which has left them worse off compared to their foundation and operating charity peers. The chart at left shows how, over the last eight years, a hypothetical $100 million investable asset pool would have performed, based on average returns from the Commonfund Benchmarks Studies. Over this period, absent spending, a foundation or operating charity would have added over $7 million more to its endowment than the average healthcare organization.

Rebalancing The Relationship

Rating agencies, bondholders and healthcare organizations have a common interest in seeing that the sector is able not only to survive the coming period of stress and transition but to thrive beyond it. To that end, a renegotiation of the strictures on asset allocation and liquidity will be necessary.

One important reason for rethinking high fixed income allocations is that, in a crisis, bonds often provide limited protection against a big loss (particularly on a forward-looking basis given today’s low yield and low spread environment). This statement seems contrary to finance textbook theory, but its truth was demonstrated in the crucible of the 2008–09 financial market crisis. In FY2008, healthcare organizations reported net investment returns of -21.2 percent while foundations reported returns of -26.0 percent and operating charities reported a nearly identical result of -25.8 percent. Healthcare organizations thus lost some 460–480 basis points less than the other two types of nonprofits, but it is impossible to say that this represented any kind of triumph of investing, particularly given the consistent and compounded underperformance of healthcare organizations’ cash- and bond-laden portfolios during the years prior to the downturn. Furthermore, in the recovery period of FY2009–FY2010, healthcare organizations have continued to underperform.

The second reason that a readjustment of asset allocations will be required is that, in the current interest rate environment, a portfolio of medium- to long-duration fixed-rate bonds—whether U.S. Treasuries or corporate credits—is extremely vulnerable to changes in the yield curve. Should 10-year interest rates rise even modestly, from the current level of below 2 percent to 4 percent or so, the adverse effect on the value of healthcare organizations’ large bond portfolios would be severe.

The Endowment Model

For all of these reasons, we submit that healthcare organizations should consider adopting the endowment model that originated in academe as leading thinkers sought better ways to manage large investment pools. The endowment model has three tenets:

-

A structural bias toward equities, meaning that equity ownership of assets is the best way to benefit from the fundamental economic growth that is the source of real, long-term returns.

-

A perpetual time horizon that positions the endowment to take advantage of the time value of invested capital, i.e., the longer an investor is willing to commit capital, the greater should be the expected return.

-

A corollary to the perpetual time horizon of these investors is their ability to exploit market inefficiencies in sectors of the capital market that suffer from a scarcity of capital owing to their illiquid nature and long-term uncertainty. Diversification matters. Long-term investors should diversify away as much risk as possible so as to own efficient portfolios and hedge fundamental risks such as inflation and deflation.

Conclusion

It is in the interest of healthcare organizations, rating agencies, and donors that healthcare endowments evolve toward becoming more like those of other long-term nonprofit institutions. The nature of many alternative investments, with their limited partnership structures, and the imperative to diversify among strategies and vintage years, means that this will be a slow process, perhaps taking as much as a decade. But, particularly for small and mid-sized healthcare organizations that lack the ability to spread costs over a wider patient base, a greater degree of reliance on endowment income appears inevitable, and there is little time to lose.

The conclusion is inescapable: Healthcare organizations will become more reliant on their endowments.

- Brinson, Hood and Beebower, “Determinants of Portfolio Performance.” Financial Analysts Journal, July/August 1986, pp. 39–44 and Brinson, Singer and Beebower, “Determinants of Portfolio Performance II: An Update.” Financial Analysts Journal, May/June 1991, pp. 40–48.