Assets under management (AUM) among hedge funds has always been characteristically top-heavy, with the majority of capital in the hands of a relatively small number of managers. While the hedge fund universe has expanded from a few hundred in the mid-1990s to several thousand today, investors have voted in large numbers for what amounts to a handful of those managers.

It is not difficult to infer why thousands of allocation decisions made independently might, as an end-result, take this shape – numerous features of hedge fund markets may push allocators upstream. For one, sourcing hedge funds is resource-intensive, and finding that thousandth-largest manager can be significantly more expensive than finding the tenth-largest.

Such resource constraints alone, however, alone do not explain away the tendency to the largest managers.

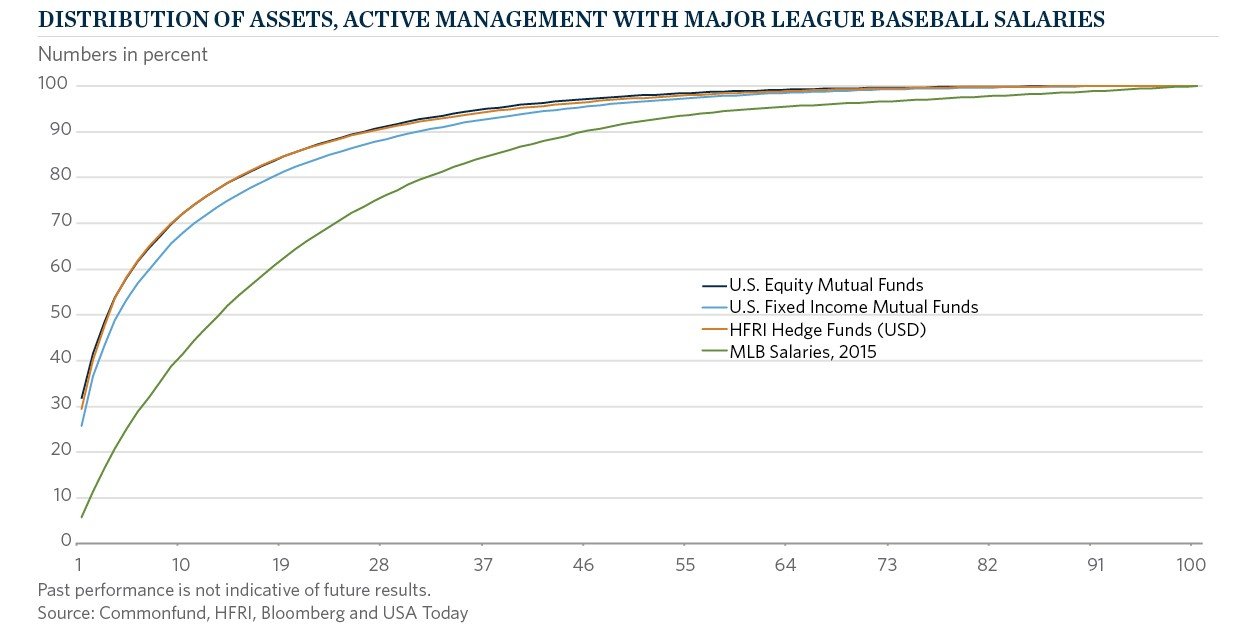

Consider the figure below, showing the cumulative distribution of AUM for all USD-denominated hedge funds reporting to HFRI alongside all US equity and US fixed income mutual funds reporting to Bloomberg. On the x-axis (left-right) is a cumulative percentage of managers by number, from 1 to 100 percent; on the y-axis, percent of assets those managers control. For frame of reference, also shown is aggregate salary data for Major League Baseball – the highest-paid players earn multiples of league-average, but it looks almost egalitarian in comparison to the assets in the active management universes.

The lopsidedness of hedge funds in particular has its critics, particularly among skeptics who see it as representative of issues unique to the industry: misaligned interests induced by fee structures, a culture of overextended growth, the irrational draw of perceived star power.

For all the hand-wringing, though, and the assumptions about why hedge fund investors allocate as they do in large scale, it is notable that amid very different sets of constraints, investor scope, fees and culture, mutual fund investors ultimately show much the same tendencies.

Perhaps, then, it is better to think of manager size, in a macro sense, not as a default that investors tend to wander into, but rather as an attribute that they value positively, all else equal, and one that, perhaps, they are willing to pay for in terms of performance. There are a number of reasons why that would be, including those features common to the largest funds that are characterized as “institutional quality,” such as multi-personnel staffs of legal, compliance, operations, and risk management.

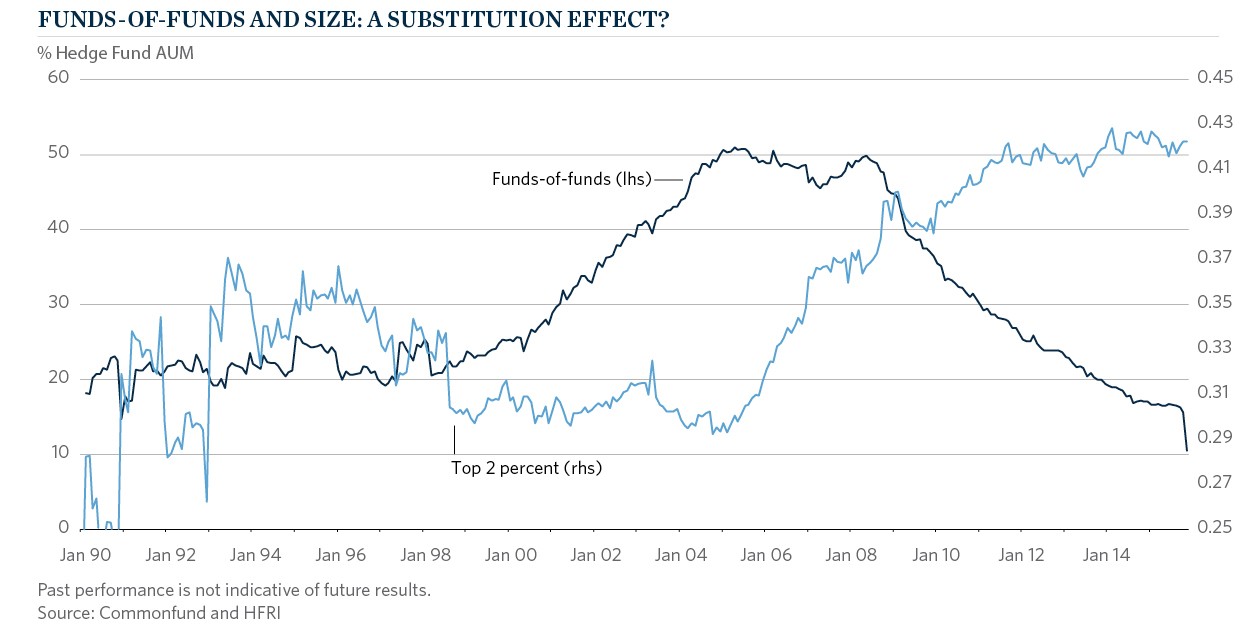

But how much are investors ultimately willing to pay, and what is that acceptable trade-off sensitive to? There may be clues to this question in how this distribution of assets has changed over time, as AUM has in the recent past only grown wobblier, investor preferences more pronounced.

It is, perhaps, not incidental that this recent growth in AUM among the largest managers has coincided with a large-scale exodus of capital from funds-of-funds. That is, as investors have migrated from funds-of-funds to direct selection of individual managers, investors acting independently may be in effect compensating for the risk-offsets formerly provided by funds-of-funds, including due diligence and diversification, with size.

It has become almost conventional wisdom that small hedge funds, on average, tend to outperform large. What was a provocative claim years ago – provocative, because it had the flavor not just of size but, by implication, top managers’ elite status and reputation – has by now been widely circulated. Chances are that anyone who allocates to hedge funds for a living is at least familiar with it.

On the face of it, then, investors routinely operate in opposition to the house advantage.