2017’s tax legislation is the latest in a growing list of challenges facing higher education. The new excise taxes on endowment earnings of the largest private universities, coupled with the not-yet-fully-understood impact of the increase in the standard deduction on overall charitable giving, may not by themselves break the proverbial bank. However, when considered in the context of broader trends, we believe fiduciaries should be vigilant that leaks don’t turn into a flood. The best way to do this is to have sound policies that govern decision making and that are formulated, and evaluated, in a cross-functional fashion across the institution. Risk identification and management that includes stress testing on an enterprise-wide basis should also be part of the protection plan.

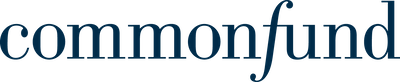

A hypothetical small private college can illustrate how these leaks could turn into a flood. With an endowment of $100 million, an operating budget of $100 million, and 2,000 undergraduates, Fictional College would not be impacted by the excise tax on endowment earnings as that tax applies to only those private institutions with endowment-per-student ratios of $500,000 or more. However, only 5 percent of Fictional College’s operating budget is supported by the endowment so net tuition revenue is a more critical factor for the school. On a national scale, enrollment peaked earlier this decade and declined on a rolling 4-year basis for the first time in a generation in 2015.

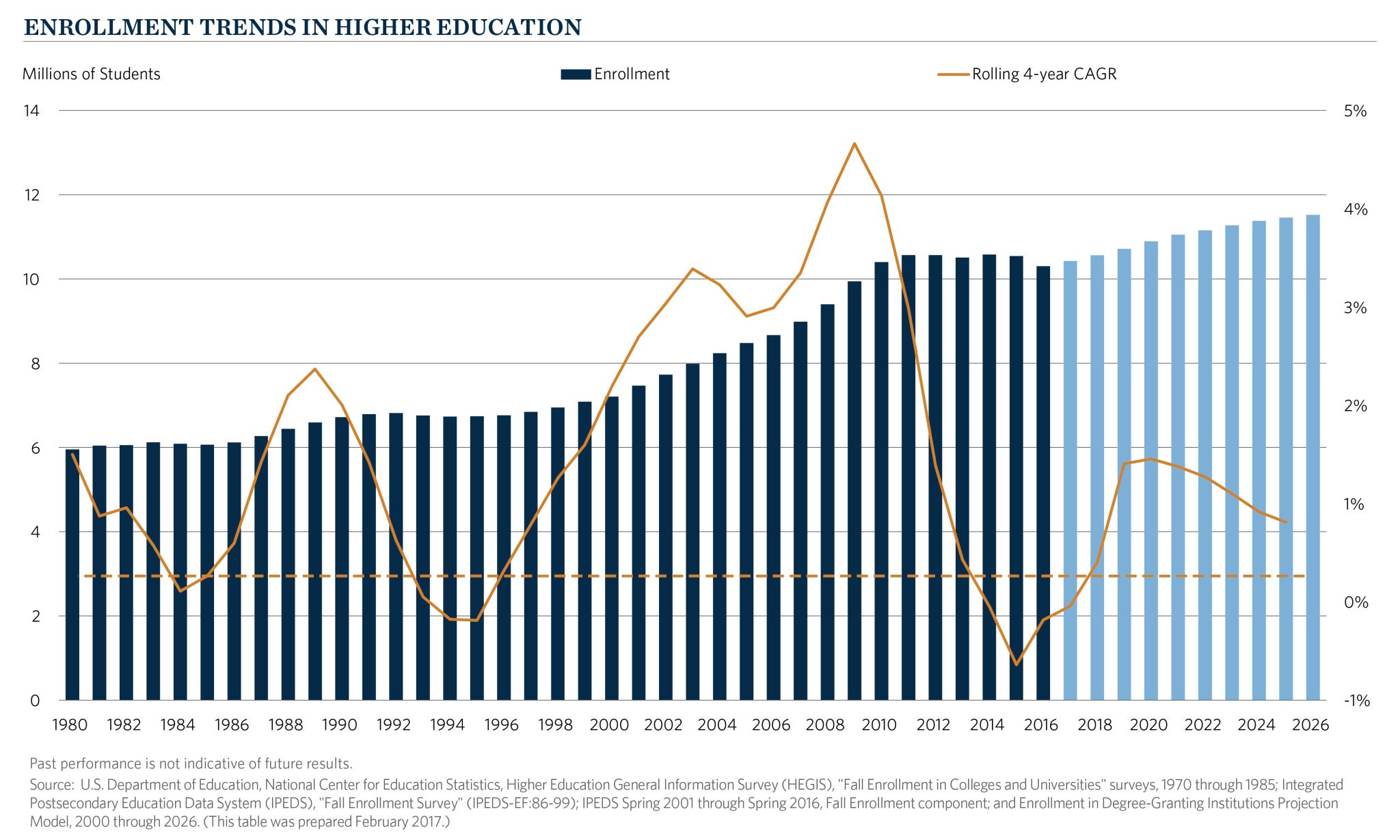

Indeed, according to NACUBO, more than half of respondents saw declines in total undergraduates or first-time freshmen and 39 percent experienced declines in both their first-time freshmen and total enrollments.1 As a result, the environment has become more competitive and many have responded with higher discount rates, which reached an estimated 49.1 percent in 2016-2017, the highest level recorded in the history of the Tuition Discounting Study project (first-time, full-time freshman).

Rising discount rates have led to much slower growth in net tuition revenue, or, for many colleges, declines in net tuition revenue. At the same time public funding has declined. In 2014-15, appropriations per full-time equivalent student were 8 percent lower in inflation-adjusted dollars than they were a decade earlier and 11 percent lower than they were 30 years earlier.2

Gifts may help the situation, but there are estimates that giving could decline up to 5 percent due to the new tax law’s higher standard deduction. Fictional College probably gets 2-5 percent of its total revenues from giving, so this may be another leak. Even before the tax legislation, charitable contributions to colleges and universities in the United States increased only 1.7 percent in 20163, a gain that was nearly eliminated when adjusting for inflation. Moreover, giving has been increasingly concentrated at the larger, more well-known institutions, with just 20 institutions (less than 1 percent), receiving 27 percent of all gifts in 2016.4

The realities of lower net tuition revenue, declining public support and lower contribution rates are happening at a time when the costs of running a higher education institution or providing a scholarship (the cost of tuition) continue to rise. The Higher Education Price Index (HEPI), which tracks a fixed market basket of goods and services purchased by colleges and universities, increased 3.7 percent in FY 2017 – the largest increase since 2008 – and the increases in tuition have been well documented.

Returning to Fictional College, we can envision a stress scenario where the leaks become a flood. If costs rose 3.7 percent, net tuition revenue declined 2 percent, endowment income remained flat, gifts dropped 5 percent and other revenue dropped 4 percent, we would see a potential deficit of almost $6 million.

Preparing for this scenario requires an integrated approach to understanding operating and financial metrics across the institution. How much flexibility is there, what is the debt capacity, what is the liquidity profile, and how are unrestricted assets treated? These are the types of questions that should be asked at the board level and across investment/finance committees, finance offices, development teams and others. From these questions, sound policies can be established, revisited or refined. And, lastly, a response plan for the next crisis, or a “crisis playbook,” is undoubtedly easier to put in place when the waters are calm and market volatility is low.

1 Source: 2016 NACUBO Tuition Discounting Study (TDS)

2 Source: Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. “Funding Up, Tuition Down”, August 15, 2016.

3 According to the Voluntary Support of Education (VSE) survey, conducted annually by the Council for Aid to Education (CAE).

4 Council for Aid to Education.