Other than the impending recession, one of 2023’s most anticipated economic changes has been a labor market slowdown, with both economists and investors expecting a deceleration in economic activity and higher unemployment by the end of 2023.

However, despite the commonly held expectations of imminent labor market weakness, the economic data has been slow to respond. Nonfarm payrolls continue to beat expectations (most recently beating the median estimate for the 12th straight month), and the unemployment rate remains at multi-decade lows in line with the muted jobless claims data. Although the labor market has been largely unresponsive to the significant monetary tightening that has occurred, there are signs that this could shift in the coming months.

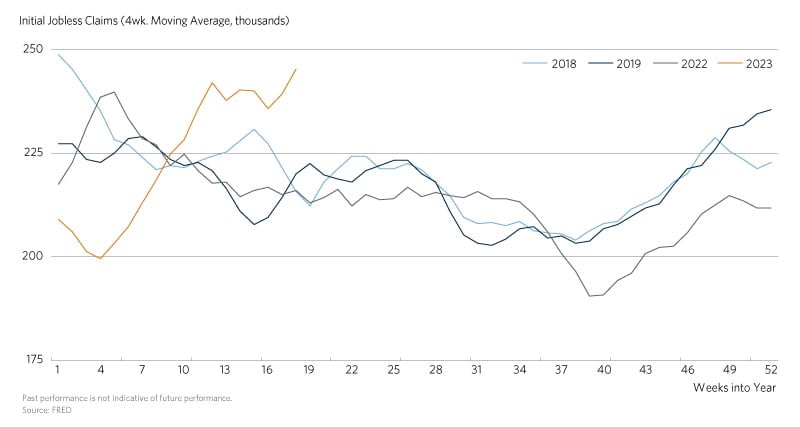

This chart of the month depicts the seasonally adjusted four-week moving average (which is a better indication of trend than the weekly release) of initial jobless claims throughout 2018, 2019, 2022, and thus far into 2023.1 After months of anticipation, there appear to be initial signs of weakness (albeit small) in the labor market. Despite having a lower starting point than each of the prior years, jobless claims have trended higher in the first 19 weeks of this year and are poised to break above 250,000, a level not seen since late 2021. On percentage terms, the four-week moving average has increased just short of 18 percent year-to-date. Additionally, the weekly initial claims level of 264,000 was the highest since October 2021 and continued claims (which measures those who have filed an additional claim for a second week of unemployment insurance) have begun to trend upward from late-2022 lows. After months of job cuts in the most interest rate-sensitive sectors, it seems that historically tight monetary policy has just begun to transmit to the broad labor market.

Other indicators support incoming labor market weakness. While nonfarm payroll growth has beaten consensus expectations, there has been a clear downward trend towards 100,000 new jobs per month since the second half of 2022 and expectations have guided down commensurately. Job openings have largely returned to pre-pandemic trend off staggering levels, and the quits rate has come down from its cyclical high of 3 percent. As indicators that tend to lead the headline unemployment rate, the combination of negative trends suggest that 4.5 percent unemployment at year-end outlined in the Federal Reserve’s Summary of Economic Projections may be closer than we think.

That said, there are reasons to believe that employment could have continued resilience. The vacancies to unemployed ratio is about 1.7, which is significantly higher than historical average (albeit trending downward from an all-time high of 2). In addition, wage growth is elevated primarily for job switchers and those in the service sector, which suggests that the lion’s share of bargaining power remains with laborers. Whether the Federal Reserve can engineer sufficient unemployment to suppress wage growth to cool inflation towards the key 2 percent target will remain hotly debated throughout 2023.

-

2020 and 2021 were omitted due to the significantly higher levels of unemployment claims following the COVID-19 shock.