With many market participants expecting low nominal returns across traditional asset classes in the coming years, the challenge of structuring a portfolio to achieve CPI +5%, or long-term purchasing power, has become even more formidable for investment committees and chief investment officers.

As part of the solution, these investors may be looking to increase their exposure to illiquid asset classes such as private equity and venture capital. The hope of capturing a liquidity premium, however, is offset by the fact that investors must enter into illiquid investment structures and therefore requires an evaluation of whether locking up capital for 10-plus years is ‘worth it.’

The answers to this question include the possibility of achieving excess return over more liquid, efficient investment strategies as well as the potential diversification benefit of investing in a universe of smaller companies not available in the public market.

Many, including Commonfund, have written about and demonstrated that, historically, a “liquidity premium” has existed in the past. Moreover, we believe it will continue to exist in the future. The potential for premium returns, however, is not the subject of this article.

Instead, we address head-on investors’ misperception about illiquid investments: they aren’t as illiquid as many fear.

For the purposes of this article, we focus on private equity, an investment strategy generally structured as 10- to 12-year partnerships. As such, there is a perception that investors lock up their capital for more than a decade. The reality is that capital is only exposed (i.e., illiquid) for a portion of that time. An investor commits to providing capital for 12 years, yet much of that commitment remains undrawn over the life of the investment.

At Commonfund Capital, for example, we typically commit to underlying private equity managers over a two- to three-year period following the final close of one of our funds. Our managers then call capital to invest in portfolio companies over an average period of three to six years. We structure our funds with a 12-year term in order to cover the full life cycle of those underlying manager investments.[1] However, each underlying company (and the resulting distribution) will, on average, have a much shorter lifecycle, as illustrated below.

Lock-up Time: A Case History

In order to determine how long private equity dollars are exposed to the market, we quantified the capital call and distribution pace for a fund-of-funds program using several different methods. We selected a U.S.-focused private equity fund-of-funds as a representative fund for our analysis. This fund was formed in January 2000 as the fourth in a series of multiple-manager, U.S. private equity programs. The fund received $452.2 million in capital commitments from investors. The fund made commitments to 16 private equity managers and has called approximately $441.3 million, or 98 percent of investor commitments to date. As of March 31, 2017, the fund had distributed $874.7 million to investors, or approximately 2.0x invested capital. We selected this fund since it was formed in the 2000s and has experienced a full private equity life cycle. Of course, past performance does not guarantee future results. This analysis is for illustrative purposes only, and does not necessarily represent the actual returns an investor may have received.

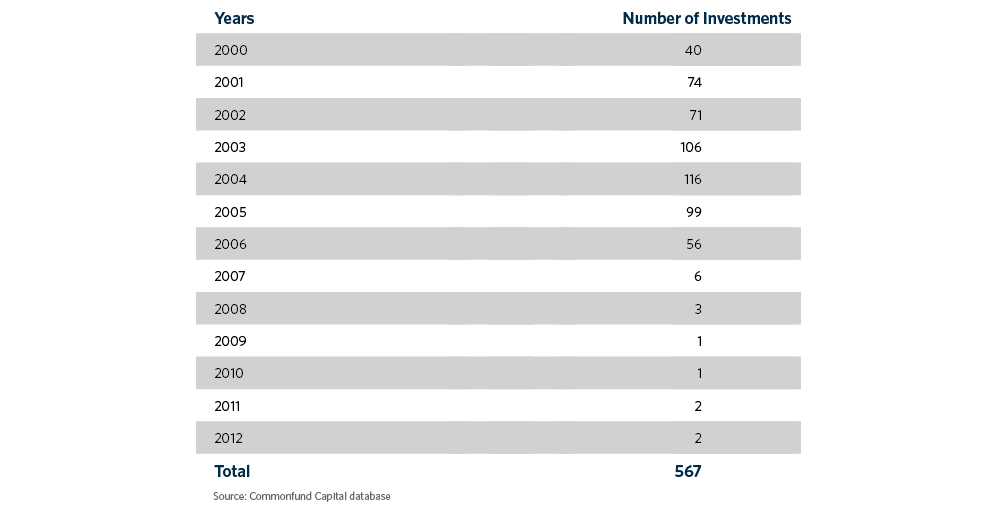

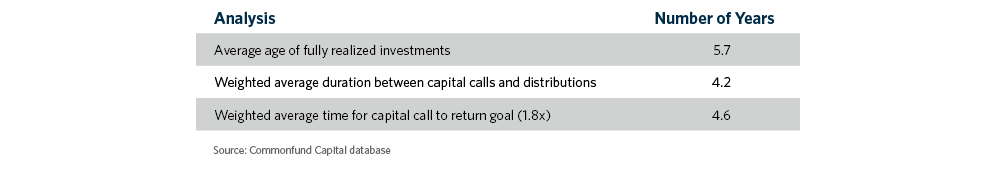

First, we looked at the average age of fully realized companies in the fund. The underlying managers in the fund invested in 576 portfolio companies with the majority of those investments made between 2001 and 2005. Approximately 480 investments in the portfolio were fully realized as of September 30, 2016, with the average time between initial investment and final exit date of those 480 realized companies being 5.7 years.

Time Between Capital Call and Distribution

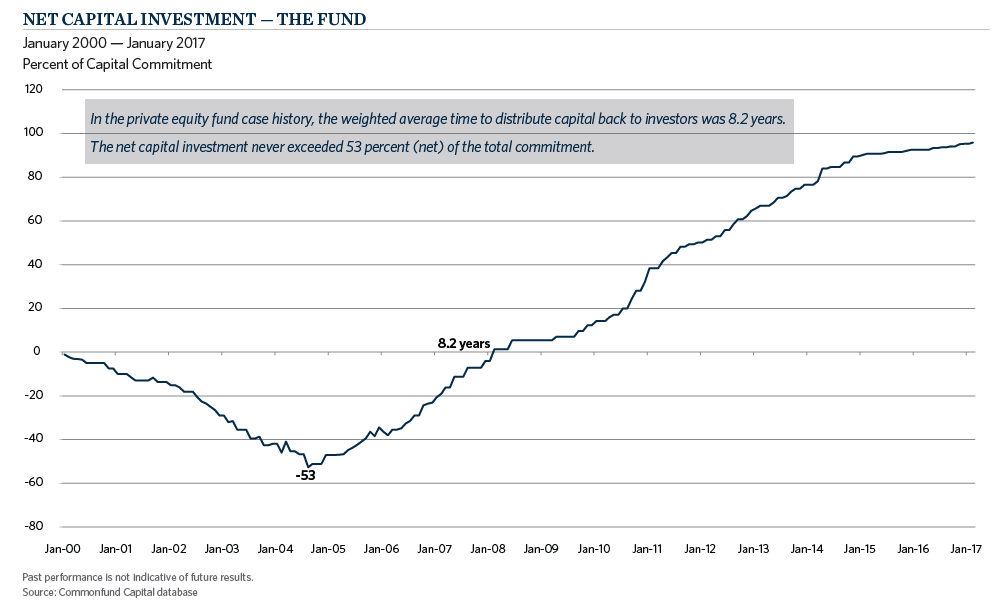

Second, we calculated a duration of the weighted average cash flows, using monthly data for the U.S. private equity program. The fund called capital from investors between January 2000 and August 2007. The average time it took to call capital, weighted by the size of the capital call, was 4.0 years. The fund first distributed capital back to investors in December 2000. The average time it took to distribute capital back to investors, weighted by the size of the distribution, was 8.2 years. The delta between the average capital call and distribution duration was 4.2 years, demonstrating that the dollar-weighted average time between capital being invested and capital being distributed is substantially less than half of the 12-year term of the fund.

The fund began distributing capital back to investors while continuing to make new commitments to managers and also making capital calls. The “net capital investment,” or percentage of investors’ capital invested, never exceeded 53 percent of the total commitment amount over the life of the fund when netted against distributions.

Return Goal On Cash Invested

Finally, we considered the average time for each capital call to achieve a return of 1.8x to investors, which is our goal for return multiples on our private equity strategies. For this analysis, we assumed the capital committed in the first capital call was returned as the first distribution, much like a first-in-first-out, or “FIFO,” calculation where the first dollar invested is the first dollar distributed. (We note that this would not always be the case as investment time periods vary widely by company.) Using this assumption, we calculated that each dollar invested returned $1.80 (1.8x) in cash back to investors within an average of 4.6 years (weighted by dollars called).

As our analysis demonstrates, it can take approximately four to five years for companies to become fully realized and capital distributed. Below is a table summarizing results of our analyses.

Conclusion

When considering their illiquidity budget and liquidity needs, institutional investors should understand the true illiquidity of a private capital program. The data cited here provides evidence that the actual time investors’ capital is locked up may be less than half of the stated 12-year life of a partnership. We also note that the private equity industry has evolved since the 2000s and more modern private equity portfolios utilize more capital efficient strategies such as secondaries and co-investments into the portfolio construction mix. These secondary transactions and co-investments have a tendency to return capital sooner and potentially shorten the overall life of a thoughtfully designed private equity investment program.

In the private equity fund case history, the weighted average time to distribute capital back to investors was 8.2 years. The net capital investment never exceeded 53 percent (net) of the total commitment.

This article was originally published in Insight Online in the Fall 2013 issue titled as “What? Me, Illiquid”.

- The life cycle of a manager’s investment generally has the following components: sourcing and performing due diligence on an investment; providing initial funding; transforming the company through value creation activities (such as growing revenues through adding product lines and geographic expansion, making strategic acquisitions, etc.); sometimes committing follow-on funding; harvesting/selling the company; and making a distribution back to investors.